In the vast and complex landscape of the American stock market, few sectors capture the imagination—and test the fortitude—of investors quite like biotechnology. It is a realm where microscopic breakthroughs can translate into billion-dollar valuations, and where the promise of curing humanity’s most devastating diseases collides with the cold, hard reality of scientific risk and regulatory hurdles. At the heart of this dynamic sector lies a particularly tantalizing, yet treacherous, segment: small-cap biotech firms.

These companies, typically with market capitalizations between $300 million and $2 billion, represent the quintessential “double-or-nothing” investment. They are the modern-day explorers, charting uncharted biological territories with novel platforms, first-in-class therapies, and ambitious scientific visions. A single positive clinical trial readout or regulatory approval can send their stock prices soaring by hundreds of percent, creating life-changing wealth for early backers. Conversely, a failed trial or an FDA Complete Response Letter (a rejection) can vaporize decades of research and capital in a single trading session.

This article, “The Biotech Bullseye,” is not a crystal ball nor a hot stock tip sheet. Its purpose is to provide a disciplined, risk-adjusted framework for analyzing these promising yet perilous enterprises. We will move beyond the hype of press releases and delve into the fundamental pillars that separate speculative gambles from calculated investments. By understanding how to assess the science, the financials, the team, and the market opportunity through a risk-aware lens, you can learn to aim for the bullseye in small-cap biotech, while rigorously managing the inherent dangers of the shot.

Section 1: The Small-Cap Biotech Ecosystem – More Than Just a Gamble

To invest intelligently in this space, one must first appreciate the unique role these companies play in the broader healthcare ecosystem.

The Innovation Engine: Large pharmaceutical companies (“Big Pharma”) are often optimized for commercialization, marketing, and incremental innovation. The truly disruptive, paradigm-shifting science frequently originates in academic labs and is spun out into small, agile biotech firms. These small-caps serve as the de facto R&D engine for the entire industry, taking on the high-risk, early-stage discovery and development that larger companies are hesitant to fund internally.

The Acquisition Lifeline: For the vast majority of small-cap biotechs, the end goal is not to become the next Pfizer or Roche. It is to de-risk their asset sufficiently—through positive mid-to-late-stage clinical data—to become an attractive acquisition target for those very same giants. This “buyout premium” is a core component of the investment thesis. As Big Pharma faces its own “patent cliff” (the expiration of blockbuster drug patents), it is perpetually hungry for new revenue streams, making successful small-caps valuable strategic assets.

The Capital Lifecycle: Small-cap biotechs are capital-intensive creatures. They typically follow a funding trajectory:

- Venture Capital & Angel Investors: Seed funding for foundational research.

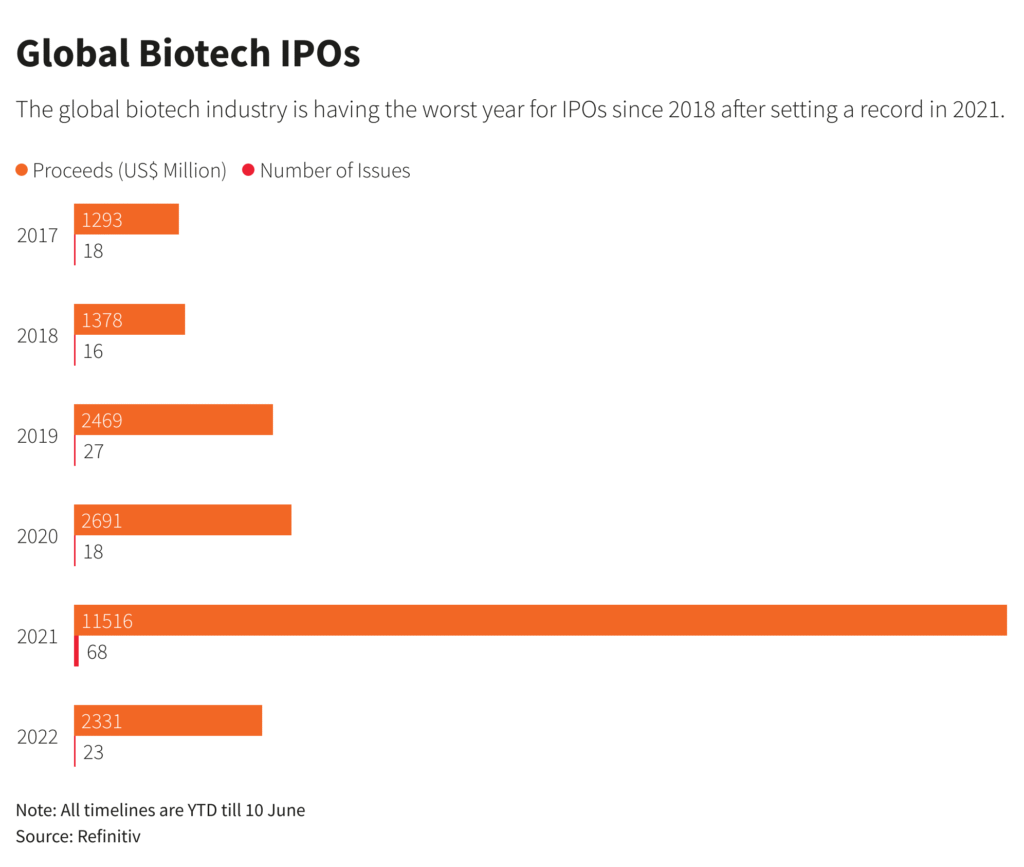

- Initial Public Offering (IPO): Accessing public markets to raise larger sums for clinical trials.

- Follow-on Offerings (Dilution): Subsequent stock offerings to fund ongoing operations, a critical risk factor for shareholders.

- Partnerships & Licensing: Non-dilutive funding from larger partners in exchange for rights to a drug in certain regions or indications.

Understanding this lifecycle is crucial, as an investor’s entry point dramatically alters their risk/reward profile.

Section 2: The Pillars of a Risk-Adjusted Analysis

A risk-adjusted analysis seeks to identify companies where the potential reward (e.g., drug approval, acquisition) justifies the multifaceted risks. It involves a multi-layered due diligence process focused on four core pillars.

Pillar 1: The Scientific Moats – Assessing the Asset and the Platform

This is the foundation. Without compelling science, nothing else matters.

- The Technology Platform vs. The Single Asset: Distinguish between companies built around a single drug candidate and those with a broader technology platform.

- Single-Asset Companies: Higher risk is concentrated in one outcome. If the lead drug fails, the company often has little fallback. The key is to assess the strength of the scientific rationale and preclinical data supporting that single asset.

- Platform Companies: These firms have a core technology (e.g., a novel drug-delivery system, a unique gene-editing tool, a proprietary antibody platform) that can generate multiple drug candidates. This diversifies risk. Even if one program fails, the platform’s value remains. Platforms with the potential to create an entire pipeline are often more valuable long-term.

- Mechanism of Action (MoA): Does the science make biological sense? Is the MoA novel, or is it a “me-too” drug chasing an established target? First-in-class drugs offer higher reward but higher risk; best-in-class drugs in a validated target class can be a lower-risk proposition.

- Clinical Trial Design & Endpoints: Scrutinize the trials themselves.

- Endpoints: Are they using validated, well-recognized endpoints that the FDA will accept? Surrogate endpoints (e.g., tumor shrinkage instead of overall survival) are faster but can be less predictive of real-world benefit.

- Trial Design: Is it a well-powered, randomized, controlled trial? Or is it a small, open-label study prone to bias?

- Statistical Significance: Look for a high bar. A p-value of <0.05 is the minimum; increasingly, investors look for p<0.01 or better to be truly convinced.

Pillar 2: The Financial Fortress – Runway, Dilution, and Dealmaking

A brilliant drug is useless if the company runs out of money before it can be developed.

- The Cash Runway: This is the most critical financial metric. Calculate it as: Cash & Equivalents / Quarterly Operating Burn Rate. A company with less than 12-18 months of runway is in a “cash crunch” zone and will almost certainly need to raise money, which dilutes existing shareholders. Look for firms with 24+ months of runway, providing a buffer against clinical delays and market volatility.

- The Dilution Diligence: Analyze the history of share count. Has the company been responsibly managing dilution, or does it constantly issue new shares at low prices to stay afloat? Check for outstanding “warrants” and “preferred stock,” which can represent future dilution.

- The Balance Sheet: Is the company carrying significant debt? While rare for early-stage biotechs, debt can be a major red flag, as interest payments accelerate cash burn.

- Non-Dilutive Funding: The hallmark of a de-risking event is a partnership or licensing deal with a major pharmaceutical company. Such a deal provides cash, validates the science, and often includes future milestone payments. It signals that sophisticated players see value in the asset.

Pillar 3: The Human Capital – Experience in the Trenches

Bet on the jockey, not just the horse. The management team and board of directors are paramount.

- Track Record: Look for a CEO and Chief Scientific Officer (CSO) who have “been there, done that.” Have they previously shepherded drugs through the FDA approval process? Have they successfully founded and sold biotech companies before? A team with a history of exits is a major positive indicator.

- Board Composition: A board with seasoned industry veterans, former FDA regulators, and renowned clinical key opinion leaders (KOLs) adds immense credibility and provides invaluable guidance.

- Big Pharma & Academic Pedigree: While not a guarantee, leadership with prior experience at top-tier research institutions or successful biopharma companies often brings a network and operational discipline that pure academics may lack.

Pillar 4: The Commercial Archery – Aiming at a Viable Market

A safe and effective drug is not a commercial success if no one will buy it.

- Target Market Size (TAM): Is the company targeting a multi-billion dollar “blockbuster” market (e.g., Alzheimer’s, NASH) or a niche “orphan” disease? Orphan drugs, for conditions affecting under 200,000 people in the US, often benefit from faster regulatory pathways, tax incentives, and the ability to command premium pricing. They can be highly profitable, albeit with a capped patient population.

- Unmet Medical Need: Drugs that address conditions with no current effective treatments have a clearer path to adoption and favorable reimbursement. How significant is the improvement over the standard of care? A marginal improvement may struggle commercially.

- Competitive Landscape: Who else is operating in this space? Are there established giants or other nimble small-caps with potentially superior drugs? A thorough competitive analysis is essential. A “me-too” drug entering a crowded market faces steep commercial headwinds, regardless of its efficacy.

- Reimbursement Risk: This is a often-overlooked but critical factor. Will insurance companies and Medicare be willing to pay for this drug, especially if it is priced at $500,000 per year? Analyzing the potential for favorable reimbursement is a key part of commercial assessment.

Section 3: A Practical Framework for Building a Risk-Adjusted Portfolio

Knowing the pillars is one thing; applying them is another. Here is a step-by-step framework for constructing a biotech portfolio.

- Start with a Thematic Screen: Don’t look for stocks; look for breakthroughs. Are you interested in gene therapy? Oncology? Neurodegenerative diseases? Start by identifying the most exciting scientific areas. Follow key opinion leaders and major medical conferences (ASCO for oncology, AAN for neurology, etc.).

- Apply the “Due Diligence Checklist”: For each company that catches your eye, run it through the four pillars:

- Science: Platform or single asset? Strong MoA? Robust trial data?

- Financials: What is the cash runway? Risk of near-term dilution?

- Team: Proven track record? Relevant experience?

- Market: Large or niche TAM? High unmet need? Manageable competition?

- Catalyst Identification and Calendarization: Biotech investing is often event-driven. The primary value-creating (or destroying) events are “catalysts.” These include:

- Clinical trial data readouts (Phase 2, Phase 3)

- Regulatory submissions (NDA, BLA) and decisions (PDUFA dates)

- Major medical conference presentations

- Partnership/acquisition announcements

Identify the next 6-18 months of known catalysts for a company. Investing without knowing the catalyst timeline is like sailing without a destination.

- Position Sizing and Diversification: The Golden Rule

This is the most important step for risk management. Never, ever bet a significant portion of your portfolio on a single small-cap biotech.- Treat each position as a venture-capital-style bet. Even with excellent due diligence, the probability of failure for any single drug candidate is high.

- Allocate a small, fixed percentage of your portfolio to each idea (e.g., 1-3%). This ensures that a single catastrophic failure does not derail your long-term financial goals.

- Diversify across therapeutic areas and technology types. If you have five oncology stocks, you are not truly diversified, as a sector-wide sentiment shift can hurt them all.

- Continuous Monitoring and The Exit Strategy:

Biotech is not a “set and forget” endeavor. Continuously monitor:- Clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov) for patient enrollment updates.

- Company press releases and SEC filings (10-Q, 10-K).

- Scientific publications and competitor news.

Have a pre-defined exit strategy. Will you take profits after a successful Phase 3 readout? Or will you hold through an FDA decision? Will you sell if the cash runway drops below 12 months? Emotional decision-making is the enemy of successful biotech investing.

Read more: How Does the Federal Reserve Impact Everyday American Borrowers?

Section 4: Illustrative Case Studies – Hits and Misses

Case Study 1: The Bullseye – Moderna, Inc. (MRNA) in its Small-CCap Days

- The Setup: In the years leading up to 2020, Moderna was a classic, yet controversial, platform-based small-cap biotech. Its mRNA technology was unproven, and it had yet to bring a product to market. Skepticism was high.

- Risk-Adjusted Analysis:

- Science: A potent platform with potential applications across infectious diseases, oncology, and rare diseases. High risk, but transformative potential.

- Financials: Despite burning cash, it had repeatedly raised capital from partners and the public market, believing in the platform.

- Team: Experienced leadership with a strong scientific foundation.

- Market: Aiming at massive, unmet needs.

- The Catalyst: The COVID-19 pandemic provided the ultimate validation event. The platform delivered a vaccine with unprecedented speed and efficacy.

- The Lesson: Platform companies with broad potential can be home runs. The risk was immense, but for those who understood the platform’s potential and sized their positions appropriately, the reward was historic.

Case Study 2: The Near Miss – Sarepta Therapeutics (SRPT)

- The Setup: Sarepta, for years, was a single-asset company focused on eteplirsen, a drug for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD).

- Risk-Adjusted Analysis:

- Science: The data was fiercely debated. The trial was small, and the endpoint (increased dystrophin) was a surrogate. The scientific community was split.

- Financials: Perpetually in a cash crunch, with high dilution risk.

- Market: A devastating disease with no cure, representing a high unmet need and a defensible orphan drug market.

- The Catalyst: In a highly controversial decision, the FDA granted accelerated approval in 2016 based on the surrogate endpoint.

- The Lesson: Regulatory risk is immense and can sometimes defy scientific consensus. Sarepta’s approval was a win for patients and shareholders, but it was a high-wire act that highlighted the non-binary nature of FDA decisions. It underscored the risk of investing in companies where the science is not universally accepted.

Case Study 3: The Wipeout – A Fictionalized Composite

- The Setup: “Company X” has a promising preclinical drug for a common solid tumor. The early mouse data is spectacular. The press releases are euphoric.

- The Flawed Analysis: An investor gets excited by the science and the story, but ignores:

- Financials: The company has only 9 months of cash.

- Catalyst: The Phase 1 trial is 18 months away.

- Diversification: The investor puts 15% of their portfolio into Company X.

- The Catalyst: The company announces a dilutive financing at a 30% discount to the market price to fund the trial. The stock plummets. Six months later, the Phase 1 trial starts slowly, and the stock drifts lower. The investor panics and sells at a 60% loss.

- The Lesson: Ignoring cash runway, near-term dilution risk, and proper position sizing can lead to total capital destruction, even if the underlying science is ultimately sound.

Conclusion: Hitting the Bullseye is a Discipline, Not an Accident

Navigating the small-cap biotech arena is not for the faint of heart. It is a sector characterized by extreme volatility, binary outcomes, and a steep learning curve. However, for the disciplined, patient, and continuously learning investor, it offers a unique opportunity to participate in genuine scientific advancement while seeking asymmetric returns.

The “Biotech Bullseye” is not achieved by chasing tips or following message board hype. It is hit by consistently applying a rigorous, risk-adjusted framework. It demands that you become a part-time scientist, a full-time financial analyst, and a stoic risk manager. You must fall in love with the due diligence process, not the stock ticker.

By focusing on the pillars of strong science, secure finances, experienced leadership, and a viable market—and by employing strict position sizing and catalyst-based investing—you can tilt the odds in your favor. You will still have failures; it is an inherent part of the process. But by managing risk above all else, you ensure that your winners can more than compensate for your losers, allowing you to stay in the game long enough to let your best investments mature into the transformative successes that make this sector so compelling.

read more: Who Are the Biggest Market Movers in the U.S. Stock Exchange?

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I’m a new investor. Is small-cap biotech a good place for me to start?

A: Generally, no. Small-cap biotech is one of the most complex and risky public market sectors. It requires a solid understanding of financial statements, scientific concepts, and regulatory processes. It is highly recommended that new investors first build a foundation with a diversified portfolio of broad-market index funds and more established, profitable companies before allocating a small, speculative portion of their capital to biotech.

Q2: Where can I find reliable information to conduct my own due diligence?

A:

- SEC Filings (EDGAR Database): The definitive source. Read 10-K (annual) and 10-Q (quarterly) reports for financials, risk factors, and pipeline updates.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: For detailed protocol, design, endpoints, and enrollment status of all clinical trials.

- Company Presentations & Websites: Investor relations sections are a starting point, but remember they are marketing documents.

- Medical & Scientific Journals: Publications in peer-reviewed journals like The New England Journal of Medicine or The Lancet provide validated data.

- Medical Conference Webcasts: ASCO, AAN, JPMorgan Healthcare Conference, etc.

Q3: What does “p-value” mean, and why is it important?

A: The p-value is a statistical measure that helps determine whether the results of a trial are likely due to the drug’s effect or simply random chance. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p<0.05) is traditionally considered “statistically significant,” meaning there’s less than a 5% probability that the result happened by chance. The lower the p-value, the more robust the result. In biotech, a p<0.001 is considered very strong.

Q4: How do I assess the risk of dilution?

A: Dilution occurs when a company issues new shares, reducing the ownership percentage of existing shareholders. To assess the risk:

- Check the cash runway (as detailed above).

- Look at the history of the share count over the last few years in the 10-K. Is it steadily increasing?

- Check the balance sheet for outstanding “warrants” and convertible notes, which represent potential future shares.

- A company with a short runway and no announced partnership is a high risk for a dilutive financing.

Q5: What is the difference between an Orphan Drug and a Blockbuster Drug?

A:

- Orphan Drug: Targets a rare disease or condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. Benefits from incentives like 7 years of market exclusivity, tax credits for clinical trials, and waived FDA fees. Often has high pricing power due to lack of alternatives.

- Blockbuster Drug: A term for a drug that generates annual revenues of over $1 billion. These typically treat widespread, chronic conditions like high cholesterol, diabetes, or depression. The market is larger, but competition is often fiercer.

Q6: What is a “Catalyst” and why is it so important?

A: A catalyst is a specific, scheduled event that has the potential to significantly change the perceived value of a company. In biotech, these are typically clinical data readouts, regulatory decision dates, or major partnership announcements. The entire investment thesis often revolves around these binary events. Investing without knowing the upcoming catalyst schedule is highly speculative.

Q7: Is it better to invest before or after a major catalyst?

A: There is no one-size-fits-all answer, and it depends on your risk tolerance.

- Before: Offers the potential for the highest return if the news is positive (“catalyst-driven investing”). However, it carries the full risk of a negative outcome.

- After: If the news is positive, you are buying after a price spike, accepting a lower potential return for significantly lower risk, as the event has successfully de-risked the company. Some investors specialize in buying the “dip” after a negative overreaction if they believe the long-term thesis remains intact.