The climate crisis is the defining challenge of our generation, but it also presents the single greatest economic opportunity of the 21st century. The transition to a net-zero global economy—encompassing energy, transportation, agriculture, and industry—requires a fundamental rewiring of our financial systems. Trillions of dollars in capital must be mobilized to fund the research, development, and deployment of climate technologies (Climate Tech) at an unprecedented scale and speed.

At the epicenter of this financial transformation are the United States’ formidable engines of capital: its banking sector and its deep, dynamic capital markets. These institutions are not passive observers but active, albeit complex, participants in financing the green transition. This article delves into the multifaceted roles they play, the evolving strategies they are deploying, the significant challenges they face, and the critical path forward for harnessing American financial might to build a sustainable future.

Part 1: The Scale of the Challenge and the Opportunity

Before assessing the role of US finance, it’s crucial to understand the magnitude of the task. Estimates from leading institutions like McKinsey & Company and the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggest that achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 requires annual global investments in energy transition technologies to soar to approximately $4.5 trillion. The United States, as the world’s largest economy and historical largest cumulative emitter, bears a significant portion of this responsibility.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 stands as a watershed moment, committing an estimated $369 billion in federal incentives for climate and clean energy. However, this public capital is designed not to fund the transition alone, but to act as a catalytic force, de-risking projects and attracting a multiple of that figure in private investment. The success of the IRA, and of the climate transition itself, therefore hinges on the ability of US banks and capital markets to bridge this multi-trillion-dollar gap.

Climate Tech is a broad umbrella, covering:

- Clean Energy Generation: Solar, wind, geothermal, advanced nuclear (fission and fusion), and green hydrogen.

- Energy Storage & Grid Modernization: Next-generation batteries, long-duration storage, and smart grid technologies.

- Low-Carbon Transportation: Electric vehicles (EVs), charging infrastructure, and sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs).

- Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS): Direct air capture and point-source capture.

- Circular Economy & Sustainable Materials: Advanced recycling, green steel, and low-carbon cement.

- Food & Agriculture: Alternative proteins, precision agriculture, and soil carbon sequestration.

Each of these sectors has distinct risk-return profiles, technological maturity, and financing needs, demanding a sophisticated and layered approach from the financial community.

Part 2: The Role of US Banks: From Lenders to Strategic Advisors

US banks are the bedrock of the American economy, and their involvement in climate tech is evolving from a niche concern to a core strategic imperative. Their role can be broken down into several key functions.

1. Commercial and Investment Banking: Project Finance and Corporate Lending

For mature, utility-scale technologies like solar and wind, project finance has been the traditional domain of large commercial banks. They provide the debt financing necessary to construct massive solar farms or offshore wind installations. The predictability of power purchase agreements (PPAs) makes these projects bankable. Post-IRA, with its long-term tax credit certainty, this activity has intensified.

For larger, established corporations transitioning their operations (e.g., automakers retooling for EV production, or industrial companies decarbonizing their processes), corporate lending and syndicated loans are essential. Banks are increasingly linking the cost of this capital to the achievement of sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs), known as sustainability-linked loans.

2. Investment Banking: Underwriting and M&A

The major Wall Street investment banks play a pivotal role in taking climate tech companies public. Underwriting Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) for companies like EV-maker Rivian or battery-tech firm QuantumScape provides them with the massive equity capital needed for scaling manufacturing. Furthermore, they facilitate the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) that are consolidating the industry, allowing larger energy or tech companies to acquire innovative startups to accelerate their transition strategies.

3. Venture Debt and Growth Capital

Beyond traditional venture capital, banks provide venture debt to promising, venture-backed climate tech startups. This form of debt is crucial as it extends a company’s runway without significantly diluting founder and early investor equity. It is used to finance capital-intensive activities like building pilot production lines or funding initial deployments before a company becomes cash-flow positive.

4. Risk Management and Advisory

Banks possess deep expertise in assessing and pricing risk. They are developing new frameworks to evaluate the physical risks of climate change (e.g., flood damage to assets) and transition risks (e.g., policy changes, stranded fossil fuel assets). This expertise is critical for advising corporate clients on their decarbonization pathways and for structuring financial products that hedge against climate-related risks.

Part 3: The Role of US Capital Markets: Democratizing Climate Investment

While banks provide crucial debt and advisory services, the vast, liquid US capital markets are the primary engine for raising equity and securitizing assets, democratizing access to climate investments for a wide range of participants.

1. Public Equity Markets

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and NASDAQ are home to a growing cohort of pure-play climate tech companies and large-cap corporations with significant climate divisions. Investment here comes from:

- Retail Investors: Through direct stock purchases or, more commonly, via Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) ETFs and Mutual Funds. These funds aggregate capital from millions of individuals and direct it toward companies meeting specific sustainability criteria.

- Institutional Investors: Pension funds, endowments, and insurance companies, which manage trillions in assets, are under increasing pressure from beneficiaries and regulators to align their portfolios with climate goals. Their massive allocations can move markets and provide stable, long-term capital for climate solutions.

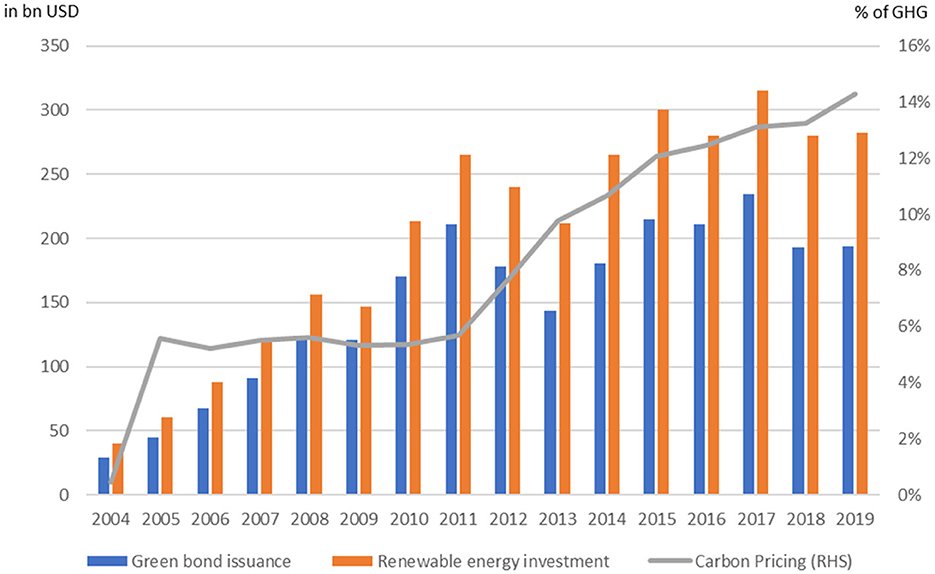

2. Green Bonds and Sustainability-Linked Bonds

The green bond market has exploded from a niche product to a mainstream asset class. Corporations, municipalities, and federal agencies issue bonds whose proceeds are exclusively dedicated to financing environmentally friendly projects. The Climate Bonds Initiative provides standards to prevent “greenwashing.” In 2023, the US was a dominant force in this market, with issuances funding everything from renewable energy projects to clean public transportation.

A related instrument, the Sustainability-Linked Bond (SLB), ties the bond’s financial terms (like the interest rate) to the issuer’s achievement of predefined sustainability targets, such as a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

3. Securitization

As the climate tech ecosystem matures, new asset classes are emerging. For example, loans for rooftop solar installations or EV leases can be bundled together and sold to investors as asset-backed securities (ABS). This process, known as securitization, frees up capital for the original lenders (like SolarCity or a specialized EV financier) to originate more loans, thereby accelerating market growth.

4. Private Markets: Venture Capital and Private Equity

The US boasts the world’s most mature and active venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) ecosystem, which is fundamental for funding the earliest and riskiest stages of climate innovation.

- Venture Capital: VC firms provide the seed, Series A, and later-stage funding for startups developing breakthrough technologies, from fusion energy to novel battery chemistries. Firms like Breakthrough Energy Ventures, founded by Bill Gates, are dedicated solely to funding climate technologies that can reduce gigatons of emissions.

- Private Equity: PE firms often invest in more mature companies, providing capital to scale proven technologies, optimize operations, or consolidate fragmented markets (e.g., in the renewable energy development space).

Part 4: Navigating the Complex Landscape: Challenges and Criticisms

The journey is far from smooth. US financial institutions face a series of interconnected challenges that complicate their role in the green transition.

1. The “Valley of Death”

This is the critical funding gap between a technology’s initial R&D (often funded by grants or early VC) and its commercialization at scale (funded by project finance or public markets). Many promising climate technologies fail in this “valley” because they are too capital-intensive for traditional VC and too risky for debt financiers who require proven cash flows. Bridging this gap requires innovative financing structures and patience.

2. Regulatory Uncertainty and Political Polarization

While the IRA provides significant incentives, the long-term regulatory landscape remains uncertain. Shifting political administrations can alter climate policies, creating risk for long-term investments. Furthermore, the intense political polarization around ESG investing has led to backlash in some states, with legislation penalizing financial institutions that are perceived to be “boycotting” fossil fuels, creating a complex and often contradictory operating environment.

3. Greenwashing and the Lack of Standardized Metrics

As demand for sustainable investments has surged, so too have concerns about greenwashing—the practice of making misleading claims about the environmental benefits of a product or company. The absence of universally accepted, mandatory, and granular disclosure standards makes it difficult for investors to distinguish genuinely sustainable companies from those making superficial claims. The SEC’s proposed climate disclosure rules and the development of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) are steps toward addressing this, but implementation and harmonization are ongoing challenges.

4. Technological and Execution Risk

Climate tech is inherently risky. A new battery technology might work in a lab but fail in mass production. A direct air capture company might struggle to bring its cost per ton down. Banks and investors must develop the expertise to underwrite these complex technological risks, which are very different from the risks associated with software or consumer goods.

5. Stranded Assets and the Legacy System

Major US banks still have significant exposure to the fossil fuel industry through their lending and underwriting activities. Managing the decline of these “stranded assets” while simultaneously financing the new energy system is a delicate balancing act. A rapid, disorderly transition could pose systemic risks to the financial system itself, a concern increasingly highlighted by central banks, including the Federal Reserve.

Read more: The Great Commercial Real Estate Reckoning: Assessing the Risks to US Regional Banks

Part 5: The Path Forward: Strategies for a Successful Transition

Despite the challenges, the direction of travel is clear. The economic opportunity is too large to ignore. For US banks and capital markets to fully realize their potential in financing the green transition, a concerted effort is required.

1. Innovation in Financial Products

The market needs more tailored products to address specific gaps. This includes:

- Blended Finance: Using public or philanthropic capital to absorb first losses and attract larger pools of private capital for risky projects in emerging markets or nascent technologies.

- Transition Finance: Developing clear frameworks to provide capital to high-emitting sectors (like steel or chemicals) for credible, measurable decarbonization projects, rather than simply divesting from them.

- Insurance Products: Creating new insurance products to mitigate the performance risk of new technologies, giving debt providers more confidence.

2. Enhanced Data and Disclosure

Financial institutions must invest in sophisticated data analytics and demand robust, audited climate data from their clients and portfolio companies. Supporting the adoption of standards from the ISSB and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is critical for building trust and enabling accurate pricing of climate risk.

3. Deepened Collaboration

No single entity can finance the transition alone. Success requires unprecedented collaboration between:

- Public and Private Sectors: Maximizing the catalytic effect of IRA funding through efficient public-private partnerships.

- Banks, VCs, and PE Firms: Creating funding syndicates that can support a company from inception through to IPO.

- Industry and Academia: Ensuring financial innovation is informed by the latest scientific and technological advancements.

4. Long-Term, Patient Capital

The climate transition is a multi-decade endeavor. It requires a shift away from short-term quarterly earnings pressure toward a mindset of long-term, patient capital. Institutional investors, with their long-duration liabilities, are ideally positioned to lead this shift, but it requires a re-evaluation of fiduciary duty to incorporate climate-related systemic risks.

Conclusion

The race to a net-zero future is both an existential imperative and the largest capital reallocation in human history. The US banking sector and its deep, innovative capital markets are not just funders but architects of this new economy. Their ability to accurately price risk, innovate financial structures, allocate capital efficiently, and navigate a complex geopolitical and regulatory landscape will ultimately determine the pace and success of the green transition.

The challenges are immense, from bridging the “Valley of Death” to combating greenwashing. However, the alignment of powerful forces—unprecedented government incentives, relentless technological innovation, and a growing drumbeat of demand from investors and consumers—is creating an irreversible momentum. By embracing their role with transparency, rigor, and a commitment to genuine impact, US financial institutions can secure their own long-term profitability while powering the solutions that will define our collective future. The financing of climate tech is no longer a sidelight; it is rapidly becoming the main event in global finance.

Read more: The Private Credit Boom: How Shadow Banking is Reshaping US Corporate Finance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. What is the difference between a green bond and a sustainability-linked bond?

- Green Bond: The proceeds are exclusively earmarked for financing or refinancing specific, eligible “green” projects (e.g., a new wind farm or a green building). The focus is on the use of proceeds.

- Sustainability-Linked Bond (SLB): The proceeds can be used for general corporate purposes. However, the bond’s financial terms (like the interest rate) are linked to the issuer’s achievement of ambitious, predefined sustainability performance targets (e.g., a 30% reduction in emissions by 2030). If the targets are missed, the interest rate may increase.

2. Aren’t banks just “greenwashing” by talking about climate while still funding fossil fuels?

This is a critical and valid concern. Many major banks are still significant funders of fossil fuel projects. The key is to scrutinize their transition plans. Look for:

- Quantifiable Targets: Are they setting concrete, science-based targets to reduce the emissions financed by their lending portfolio (their “financed emissions”)?

- Sector Policies: Do they have public policies restricting financing for the most carbon-intensive activities (e.g., Arctic drilling, thermal coal mining)?

- Capital Allocation: Is their financing for green projects growing significantly faster than their fossil fuel financing?

True leadership requires a transparent and accountable plan to align their entire portfolio with a net-zero pathway, not just highlighting green initiatives.

3. As an individual investor, how can I participate in financing climate tech?

You have several accessible options:

- ESG ETFs and Mutual Funds: Invest in funds that focus on clean energy or broad ESG criteria (e.g., iShares Global Clean Energy ETF, SPDR S&P 500 ESG ETF). Always read the prospectus to understand their specific strategy.

- Green Bonds: Some green bonds are available to retail investors, though the market is primarily institutional.

- Brokerage Accounts: Invest directly in publicly traded companies leading the charge in sectors like renewable energy, EVs, or energy storage.

- Specialized Platforms: For accredited investors, platforms like Wunder Capital (for solar projects) or others offer opportunities to invest directly in specific climate projects.

4. What is the “Valley of Death” and why is it such a problem for climate tech?

The “Valley of Death” refers to the stage where a technology has been successfully demonstrated in a lab or pilot setting but requires massive capital (often tens to hundreds of millions of dollars) to build a first-of-its-kind commercial-scale factory or deployment. Traditional venture capital may be insufficient, and project finance lenders see the technology as too unproven. This funding gap causes many promising innovations to fail before they can reach the market and achieve cost reductions through scale.

5. How is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) changing the game for private finance?

The IRA is a paradigm shift for three main reasons:

- Long-Term Certainty: Its tax credits are in place for 10+ years, giving investors and developers a predictable horizon for planning large projects.

- Technology Neutrality: It supports a wide range of solutions—from solar and wind to hydrogen, nuclear, and carbon capture—allowing the market to pick winners.

- Transferability & Direct Pay: These provisions make the tax credits more accessible and liquid. Companies that don’t have large tax liabilities can now sell their credits to other entities for cash, or in some cases (like non-profits and municipalities) receive a direct cash payment. This dramatically expands the pool of potential investors and simplifies financing.

6. Is climate tech a good investment from a purely financial perspective, separate from the environmental benefits?

Increasingly, yes. The global macro trend is unequivocally toward decarbonization, driven by policy, corporate demand, and consumer preferences. Companies that provide solutions are positioned for massive growth. However, like any emerging sector, it carries risk. There will be winners and losers. The key for investors is to conduct thorough due diligence, understand the specific technology and business model, and maintain a diversified portfolio rather than betting on single companies. The long-term growth trajectory of the entire sector, however, is considered by many analysts to be exceptionally strong.