For decades, the dominant narrative for most individual investors has been a simple one: “Just buy an index fund like the S&P 500 and hold it for the long term.” This passive approach, which champions broad market exposure at a low cost, has been a tremendous force for good, rescuing countless portfolios from the pitfalls of stock-picking and market timing.

But what if there was a more nuanced, evidence-based way to structure a portfolio? A methodology that sits squarely between the simplicity of passive indexing and the high-stakes gamble of active stock selection? This is the realm of factor investing—a sophisticated strategy that seeks to systematically identify and harness the persistent drivers of stock returns to potentially enhance performance and manage risk.

This article will serve as a deep dive into factor investing within the U.S. stock market. We will demystify the academic foundations, explore the major factors that have historically delivered excess returns, provide practical implementation strategies, and crucially, outline the significant risks involved. Our goal is to equip you with the knowledge to understand this powerful approach, allowing you to make more informed decisions about your investment journey.

Beyond the Benchmark: The “Why” of Factor Investing

The core premise of factor investing is that the stock market’s returns are not a monolithic force. Instead, they can be decomposed into distinct, measurable sources of risk and return, known as “factors.” Some of these factors compensate investors for taking on higher risk, while others seem to exploit behavioral biases or structural constraints in the market.

The intellectual underpinnings of factor investing date back to the 1960s with the development of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The CAPM introduced the concept of “beta”—a single factor representing an asset’s sensitivity to overall market movements. According to CAPM, the only way to reliably earn higher returns was to take on more market risk (higher beta).

However, by the 1970s and 1980s, empirical evidence began to pile up, showing that beta alone could not explain the performance disparities between different stocks. Academics Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, in their seminal 1992 paper, expanded the model to include two additional factors: Size and Value. This Fama-French Three-Factor Model was a revolution, explaining over 90% of the returns in a diversified stock portfolio. Later, a fourth factor, Momentum, was widely accepted, and a fifth, Profitability, was added to create a robust five-factor model.

This evolution from a one-factor to a multi-factor world is the bedrock of modern factor investing. It acknowledges that the market is complex and that by targeting specific, well-researched characteristics, investors can potentially “harvest” long-term returns that exceed those of the broad market.

Deconstructing the Market: The Core Factors Explained

Let’s move from theory to practice by examining the most established and well-researched factors. Understanding their definitions, rationales, and historical contexts is the first step toward building an effective factor portfolio.

1. The Market Factor (Beta)

This is the foundational factor. It represents the excess return of the stock market over a “risk-free” asset, typically short-term U.S. Treasury bills. When you buy an S&P 500 index fund, you are primarily capturing the market factor. All other factors are designed to provide a return in addition to this market beta.

2. The Size Factor (Small-Cap)

- What it is: The tendency of stocks with smaller market capitalizations (small-caps) to outperform larger, blue-chip stocks over the long term.

- The Rationale: There are two primary explanations:

- Risk-Based: Smaller companies are inherently riskier. They have less access to capital, are more vulnerable to economic downturns, and have a higher risk of failure. The higher return is thus a premium for bearing this additional risk.

- Behavioral-Based: Small-cap stocks are less liquid and receive less coverage from Wall Street analysts, leading to greater mispricing opportunities that can be exploited.

- How to Access: Through indexes like the Russell 2000 or the S&P SmallCap 600.

3. The Value Factor

- What it is: The tendency of stocks that are “cheap” relative to their fundamental value to outperform stocks that are “expensive.” Value is typically measured by metrics like Price-to-Book (P/B), Price-to-Earnings (P/E), or Price-to-Cash-Flow.

- The Rationale:

- Risk-Based: Value stocks are often companies in distress or facing headwinds. Their lower price reflects this higher risk, and the premium is compensation for the possibility that the company may not recover.

- Behavioral-Based: Investors tend to over-extrapolate recent poor performance into the future, becoming overly pessimistic about out-of-favor companies. Conversely, they become overly optimistic about “glamorous” growth stocks, bidding their prices to unsustainable levels. Value investing exploits this pessimism.

- How to Access: Through indexes like the Russell 1000 Value or via fundamental metrics in actively managed funds.

4. The Momentum Factor

- What it is: The tendency of stocks that have performed well in the recent past (e.g., the last 3-12 months) to continue performing well in the near future, and for recent losers to continue losing.

- The Rationale: This factor is almost entirely explained by investor psychology.

- Behavioral-Based: Investors are slow to react to new information. They underreact initially, causing a trend to develop, and then overreact later, perpetuating the trend. This is driven by cognitive biases like anchoring and herding.

- Implementation Note: Momentum is known for having sharp, violent reversals (“momentum crashes”), making it one of the more challenging factors to capture effectively.

- How to Access: Often requires a more sophisticated, rules-based approach, as it involves frequent rebalancing.

5. The Quality Factor

- What it is: The tendency of companies with robust financial health to outperform those with weak financials. Quality is measured by metrics such as high return on equity (ROE), stable earnings growth, low debt-to-equity ratios, and strong cash flows.

- The Rationale:

- Risk-Based: “High-quality” firms are less risky because they have durable competitive advantages (economic moats), strong balance sheets to weather recessions, and reliable earnings streams. In a world obsessed with “story stocks,” the steady, boring performance of quality firms can be mispriced.

- Behavioral-Based: Investors may overpay for speculative, low-quality companies with a compelling narrative, while neglecting the steady compounders.

- How to Access: Through indexes or ETFs that screen for profitability, earnings stability, and financial leverage.

6. The Low Volatility Factor

- What it is: The counter-intuitive phenomenon where stocks with lower-than-average price volatility tend to deliver higher risk-adjusted returns than their more volatile counterparts.

- The Rationale: This is a direct challenge to the core tenet of CAPM that higher risk (volatility) should equal higher return.

- Behavioral-Based: This is largely attributed to investor behavior. Many investors are attracted to “lottery ticket” stocks—highly volatile names with a small chance of a huge payoff. This speculative demand drives up their prices and suppresses their future returns. Conversely, stable, “boring” stocks are neglected, allowing them to be purchased at more attractive prices.

- Leverage Constraints: Many institutional investors are prohibited from using leverage. To achieve higher returns, they are forced to overweight high-volatility stocks instead of leveraging a portfolio of safer, low-volatility stocks.

- How to Access: Through ETFs that track minimum-variance or low-volatility indexes.

The Practitioner’s Playbook: How to Implement Factor Investing

Understanding the theory is one thing; building a portfolio is another. Here are the primary methods for implementing a factor strategy.

1. Long-Only Factor Tilts (The Most Common Approach for Individuals)

This involves using low-cost ETFs or mutual funds that overweight a specific factor while still maintaining broad exposure to the U.S. market. For example, instead of holding a vanilla S&P 500 fund, you might allocate a portion of your portfolio to:

- A Small-Cap Value ETF (targeting Size and Value)

- A Quality Factor ETF (targeting profitable, stable companies)

- A Low Volatility ETF (to reduce overall portfolio drawdowns)

This approach is accessible, cost-effective, and avoids the complexities of short-selling.

2. Multi-Factor Funds

Recognizing that factors go in and out of favor, the financial industry has created “all-in-one” multi-factor funds. These ETFs or mutual funds bundle several factors (e.g., Value, Quality, Momentum, and Low Size) into a single, rules-based portfolio. The goal is to provide more consistent returns by ensuring that if one factor is underperforming, another may be picking up the slack.

3. Smart Beta

This is a marketing term that largely overlaps with factor investing. It refers to strategies that use alternative index construction rules compared to traditional market-cap-weighted indexes. Instead of weighting companies by their size, a smart beta fund might weight them by fundamentals (e.g., sales, dividends, book value) or volatility, effectively tilting towards one or more factors.

The Crucial Caveats: Risks and Challenges of Factor Investing

Factor investing is not a magic bullet. Its historical success is no guarantee of future performance, and it comes with a unique set of risks that every investor must understand.

1. Factor Cyclicality and Prolonged Underperformance

This is the single greatest challenge. Factors can, and do, experience deep and long-lasting periods of underperformance, often lasting for several years.

- The Value Drought: The value factor, for instance, suffered a brutal decade of underperformance from approximately 2017 to 2021, crushed by the dominance of mega-cap growth stocks like the “Magnificent Seven.”

- Psychological Toll: An investor may intellectually believe in the value premium, but watching their value-tilted portfolio lag the soaring S&P 500 for years on end is psychologically grueling. Many investors abandon the strategy at the worst possible time—right before a potential rebound.

2. Implementation Costs and Fees

While factor ETFs are cheap relative to active management, they are often more expensive than plain-vanilla index funds. Trading costs, bid-ask spreads, and higher turnover (especially for momentum) can erode the factor premium. An investor must be confident that the expected premium will be large enough to overcome these additional costs.

3. Crowding and Arbitrage Away

As factor investing has become more popular, there is a risk that the premiums will be “arbitraged away” as too much capital chases the same strategies. If everyone is buying the same set of cheap, high-quality, small-cap stocks, their prices will rise, eliminating the very value opportunity that made them attractive.

4. Data Mining and Factor Proliferation

With enough data, researchers can find seemingly significant patterns that are, in fact, just statistical noise. The academic community has identified hundreds of “factors,” but only a handful have stood the test of time, out-of-sample testing, and strong theoretical grounding. Investors must stick to the well-established, economically intuitive factors to avoid being seduced by a spurious backtest.

Read more: From Accumulation to Distribution: Crafting Your Retirement Withdrawal Strategy

Building a Robust Factor Portfolio: A Strategic Framework

Given these risks, how should a thoughtful investor proceed?

- Start with a Core Foundation: Your core portfolio should still be a low-cost, broad-market U.S. index fund (the Market factor). This ensures you capture the market’s return and never dramatically underperform it.

- Apply Deliberate, Moderate Tilts: Allocate a smaller, strategic portion of your portfolio (e.g., 10-30%) to factor tilts. Instead of going “all-in” on one factor, consider a multi-factor approach to diversify your sources of return and smooth the journey.

- Embrace a Long-Term Horizon: Factor investing requires a commitment measured in decades, not years. You must be prepared to stick with your strategy through inevitable periods of underperformance. Rebalance systematically to maintain your target factor exposures.

- Prioritize Low Costs: Scrutinize expense ratios and choose the most cost-effective vehicles. A few basis points can make a huge difference over 20+ years.

- Manage Your Expectations and Your Behavior: The greatest risk to a factor strategy is not the strategy itself, but the investor’s own behavior. Write down your investment philosophy in an “investor’s statement” to remind yourself of your long-term plan during times of market stress.

Conclusion: A More Intelligent Path to Market Returns

Factor investing represents a maturation of the passive investing revolution. It moves us from the question of “Should I be active or passive?” to the more sophisticated question: “**How* should I be passive?*”

By understanding the deep, academic roots of what has driven stock returns, investors can construct more resilient, efficient, and potentially higher-performing portfolios. It is a discipline that demands patience, fortitude, and a willingness to diverge from the crowd. While it is not for everyone, for those willing to educate themselves and commit for the long haul, factor investing offers a powerful framework for systematically harvesting the risk premiums that have been embedded in the U.S. stock market for nearly a century.

The journey to harvesting higher returns is not about finding a secret shortcut; it’s about having a better map and the conviction to follow it, even when the path gets rough.

Read more: Sector Rotation: A Tactical Strategy for Navigating the U.S. Economic Cycle

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is factor investing just a fancy form of active management?

This is a nuanced question. Pure passive investing involves tracking a market-cap-weighted index without any discretion. Pure active management involves a manager making subjective bets. Factor investing sits in the middle, often called “systematic active” or “rules-based active.” It is passive in the sense that it follows a transparent, rules-based methodology, but it is active in that it deliberately deviates from the market-cap-weighted benchmark. The key is that the “active” decision is made once—when you choose and weight your factors—and then the process is automated.

Q2: Which single factor is the best to invest in?

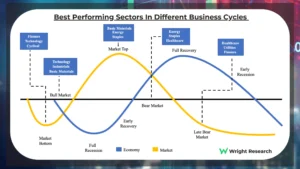

There is no single “best” factor. The performance of factors is highly cyclical. What works in one macroeconomic environment (e.g., high-interest rates, recession) may not work in another (e.g., low-interest rates, economic expansion). The value factor, for example, may perform well during periods of high inflation, while the quality factor may shine during market downturns. This is precisely why a multi-factor approach is generally recommended for most investors, as it provides diversification across different economic regimes.

Q3: How long do I need to hold a factor investment to see results?

You should have an investment horizon of at least one full market cycle, which is typically 7-10 years, but preferably longer. Factors can underperform for periods of 5, 10, or even more years. An investor who gives up on a factor after 3-4 years of underperformance is likely to miss out on the subsequent rebound that generates the long-term premium. Factor investing is a marathon, not a sprint.

Q4: Can I use factor investing in my retirement account (e.g., IRA, 401(k))?

Absolutely, and it can be an excellent place to do so. The tax-advantaged nature of IRAs and 401(k)s is ideal for factor strategies, which can sometimes have higher turnover, potentially generating short-term capital gains in a taxable account. Many 401(k) plans now offer “collective investment trusts” (CITs) that employ factor or smart-beta strategies. For your IRA, you can easily purchase the factor ETFs mentioned throughout this article.

Q5: How does the current economic environment (high inflation, rising rates) impact factor performance?

Historically, different factors have reacted differently to economic regimes:

- Value: Tends to perform better in environments of rising inflation and interest rates, as many value stocks are in sectors like energy and finance, which benefit from such conditions.

- Quality: Often performs well during economic slowdowns or recessions, as investors flock to companies with strong balance sheets and stable earnings.

- Low Volatility: Typically provides strong downside protection during market corrections, regardless of the economic cause.

It’s important to note that while these are historical tendencies, they are not guarantees. Chasing the factor that performed best last year is a form of performance chasing and is unlikely to be a successful long-term strategy.

Q6: Are there any factor ETFs you recommend?

As an impartial guide, I cannot provide specific investment recommendations. However, I can point you toward well-known, low-cost ETF providers who offer a wide range of single and multi-factor products. When conducting your own research, look at providers like iShares, Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), Vanguard, Invesco, and J.P. Morgan. Key criteria to compare are:

- Expense Ratio: The annual fee.

- Assets Under Management (AUM): A larger fund is generally more stable.

- Underlying Index/Methodology: Understand the rules the fund follows.

- Tracking Error: How closely it follows its stated strategy.

Always read the fund’s prospectus before investing.

Q7: Is it too late to start factor investing? Have the premiums disappeared?

This is a subject of lively debate. While some argue that increased popularity has diminished the premiums, the core economic and behavioral rationales for their existence remain. Companies in distress (Value) will always be riskier, investors will always overreact to news (Momentum), and people will always chase lottery tickets (Low Volatility). The premiums may not be as large as they were in the early days of their discovery, but the evidence suggests they persist, albeit with the same cyclicality and long periods of hardship as always. The key is to have realistic expectations that the excess returns, if they materialize, will be achieved over a very long time horizon.