The stock market is not a monolith; it’s a dynamic ecosystem comprised of distinct sectors, each representing a different segment of the economy. Technology, healthcare, energy, consumer staples, and financials—these sectors do not move in lockstep. At any given time, some are thriving while others are languishing. This divergence is not random chaos but is often a rational response to the prevailing phase of the U.S. economic cycle.

For the long-term investor, a simple “buy and hold” strategy in a broad market index fund can be a powerful path to wealth creation. However, for those seeking to potentially enhance returns, manage risk, or simply gain a deeper understanding of the market’s inner workings, a tactical approach known as sector rotation offers a compelling framework.

Sector rotation is the strategic practice of shifting investment assets from one stock market sector to another in an effort to anticipate and profit from the predictable shifts in economic conditions. It is based on the observation that certain sectors consistently outperform or underperform during specific phases of the economic cycle.

This article will serve as a detailed guide to sector rotation. We will deconstruct the classic U.S. economic cycle, map sector performance to each phase, provide a practical framework for implementation, and crucially, outline the significant risks involved. Our goal is not to promise a foolproof trading system but to equip you with the expert knowledge and strategic perspective needed to make more informed, confident investment decisions.

Understanding the Foundation: The U.S. Economic Cycle

Before we can rotate sectors, we must first understand what we are rotating around. The U.S. economy, like all modern economies, moves in a recurring, though not perfectly regular, sequence of expansion and contraction. This cycle is typically broken down into four distinct phases:

- Early Cycle (Recovery): This phase begins as the economy troughs and starts its recovery from a recession. Key characteristics include:

- Monetary Policy: Interest rates are low and often being cut further by the Federal Reserve to stimulate borrowing and investment.

- Economic Indicators: GDP growth turns positive, corporate earnings begin to rebound from depressed levels, and business confidence starts to improve.

- Sentiment: Investor sentiment is often still cautious, but is gradually shifting from pessimism to optimism.

- Mid-Cycle (Expansion): This is typically the longest and most stable phase of the cycle. The recovery matures into a sustained, healthy expansion.

- Monetary Policy: Interest rates may begin to slowly rise from their lows as the Fed shifts from stimulus to a more neutral stance.

- Economic Indicators: GDP growth is solid and broad-based, corporate earnings are strong, and employment levels are high.

- Sentiment: Confidence is high among both consumers and businesses.

- Late Cycle (Slowdown): The economic expansion begins to show signs of age. Growth peaks and starts to decelerate.

- Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve is often actively raising interest rates to combat rising inflation and cool down an “overheating” economy.

- Economic Indicators: Key indicators like housing starts and manufacturing activity may slow. Corporate earnings growth becomes more challenging, and profit margins may peak.

- Sentiment: Investor euphoria can set in, but smart money begins to grow cautious. Volatility often increases.

- Recession (Contraction): The economy experiences a broad-based contraction.

- Monetary Policy: The Fed aggressively cuts interest rates and may employ other tools to provide economic stimulus.

- Economic Indicators: GDP declines for two consecutive quarters, corporate earnings fall sharply, and unemployment rises significantly.

- Sentiment: Widespread pessimism and fear dominate the market.

It is critical to remember that these cycles are not clockwork. Their duration and intensity can vary dramatically. However, the sequence of phases provides a reliable model for understanding the macroeconomic backdrop against which sectors perform.

The Sector Rotation Model: A Visual and Practical Guide

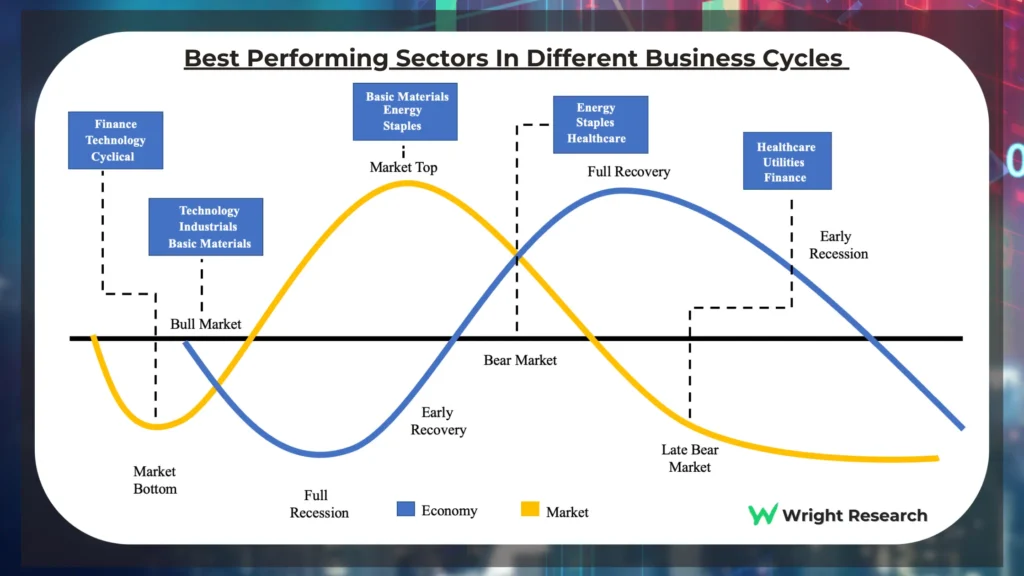

The sector rotation model visually maps the outperformance of specific sectors onto this economic cycle. The most famous representation is the sector rotation “clock” or “wheel.” While various analysts may use slightly different categorizations, the underlying logic remains consistent.

For this guide, we will use the 11 sectors of the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS), which is the framework used by S&P and MSCI and is the basis for most modern sector-based ETFs and analysis.

Here is a detailed breakdown of which sectors tend to lead, lag, and why in each phase.

Phase 1: Early Cycle – The Rebirth of Risk

As the economy emerges from recession, the primary drivers are easy monetary policy, rebounding demand, and the first signs of sustainable growth. The sectors that benefit most are those that are most sensitive to the economic recovery and low interest rates.

Leading Sectors:

- Cyclical Consumer Discretionary (XLY): When the economy picks up, one of the first things consumers feel comfortable doing is spending on non-essentials. Pent-up demand for cars, appliances, luxury goods, and travel is unleashed. Companies like Amazon, Home Depot, and Starbucks are classic examples.

- Technology (XLK): Businesses, seeing improved prospects, begin to increase capital expenditures (CapEx). A significant portion of this spending goes toward technology—upgrading hardware, software, and IT infrastructure to boost productivity. This sector thrives on low interest rates, which make financing new projects cheaper.

- Financials (XLF): Banks and other financial institutions are prime beneficiaries of the early cycle. A steepening yield curve (the difference between short and long-term interest rates) boosts their net interest margins—the profit from borrowing short and lending long. Furthermore, loan losses from the recession peak and begin to decline, while loan demand starts to pick up.

Lagging Sectors:

- Defensive sectors like Utilities (XLU) and Consumer Staples (XLP) tend to underperform as investors flee their “safe haven” status in search of higher growth.

- Energy (XLE) may still be sluggish if industrial demand has not fully recovered.

Phase 2: Mid-Cycle – Sustained Growth and Selectivity

The economic recovery is now confirmed and broadening. Growth is robust, but the “easy money” has been made in the early-cycle leaders. The market becomes more selective, rewarding companies with strong actual earnings and growth trajectories.

Leading Sectors:

- Technology (XLK): The sector often continues its leadership as corporate earnings remain strong and technological innovation drives efficiency across the economy.

- Industrials (XLI): A strong, sustained expansion means companies are investing heavily in equipment, machinery, and infrastructure. Industrials, which include aerospace, defense, construction, and logistics, are direct beneficiaries of this increased CapEx and global trade.

- Materials (XLB): As industrial activity and construction boom, the demand for raw materials—such as chemicals, metals, and mining products—increases, driving prices and profits for companies in this sector.

Lagging Sectors:

- Defensive sectors continue to lag as the “risk-on” sentiment persists.

- Early-cycle leaders like Discretionary may see their growth rates normalize, though they can still perform well.

Phase 3: Late Cycle – Defensive Shifts and Inflation Hedges

The economy is running hot. Inflation becomes a primary concern for the Federal Reserve, which is now hiking interest rates. Growth becomes more expensive to finance, and investor sentiment shifts from growth-seeking to capital preservation.

Leading Sectors:

- Energy (XLE): In an inflationary environment, hard assets often perform well. Energy, particularly oil and gas, is a direct beneficiary of rising prices. Strong global demand also contributes to its strength.

- Materials (XLB): Similar to Energy, materials companies can often pass on higher input costs to customers, acting as an inflation hedge.

- Defensive Sectors Begin to Shine: As volatility increases and growth fears mount, investors start rotating into sectors known for their stable earnings and dividends, regardless of the economic climate.

- Consumer Staples (XLP): People still buy food, beverages, and household goods in a slowdown. These companies have highly predictable revenue streams.

- Healthcare (XLV): Demand for medicines and medical services is largely non-discretionary, providing insulation from economic downturns.

Lagging Sectors:

- Technology (XLK) and Discretionary (XLY): These growth-oriented sectors are often the hardest hit by rising interest rates, which reduce the present value of their future earnings. They become vulnerable to valuation compression.

- Financials (XLF): While banks can benefit from higher rates, if the Fed’s tightening is too aggressive, it can invert the yield curve and trigger a credit crunch, which is negative for financials.

Phase 4: Recession – The Flight to Safety

The economy is in contraction. Corporate earnings are falling, unemployment is rising, and fear is pervasive. The primary goal for investors is capital preservation.

Leading Sectors:

- Defensive Sectors Dominate:

- Consumer Staples (XLP) and Healthcare (XLV) remain resilient due to their inelastic demand.

- Utilities (XLU): Despite being interest-rate sensitive, their regulated, monopoly-like business models provide extremely predictable cash flows and high dividend yields, which are highly attractive in a downturn.

- Real Estate (XLRE) (with a caveat): Certain types of real estate, like healthcare and industrial REITs, can be defensive. However, REITs as a whole are sensitive to rising interest rates and an economic downturn can hurt property values and occupancy rates. Their performance is nuanced.

Lagging Sectors:

- All cyclical sectors typically suffer severe declines. Technology, Discretionary, Industrials, and Financials often experience the deepest earnings cuts and valuation multiple contractions. These are the sectors to be underweighted or avoided during a confirmed recession.

A Practical Framework for Implementing a Sector Rotation Strategy

Knowing the theory is one thing; implementing it is another. Here is a step-by-step guide to putting a sector rotation strategy into practice.

Step 1: Diagnose the Economic Environment

You cannot rotate effectively if you don’t know where you are. This is the most challenging aspect of the strategy. Rely on data, not headlines or emotions. Key indicators to monitor include:

- Leading Economic Indicators (LEI): A composite index published by The Conference Board designed to signal peaks and troughs in the cycle.

- ISM Manufacturing & Services PMI: Readings above 50 indicate expansion, below 50 contraction. The trend is key.

- Employment Data: Non-farm payrolls and the unemployment rate.

- Inflation Data (CPI & PCE): The Fed’s primary gauge for interest rate decisions.

- Yield Curve: An inverted yield curve (when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates) has been a historically reliable, though not perfect, precursor to recession.

- Federal Reserve Statements & Dot Plot: The Fed’s outlook on growth and interest rates is a powerful driver of market expectations.

Step 2: Allocate According to the Phase

Once you have a hypothesis on the economic phase, adjust your portfolio’s sector weightings accordingly. The easiest way to do this is through Sector ETFs. Instead of picking individual stocks, you can buy or sell an ETF that tracks an entire sector.

- To overweight a sector, you would allocate a higher percentage of your portfolio to it than its weight in a broad benchmark like the S&P 500.

- To underweight a sector, you would allocate a lower percentage.

Example Allocation Shift:

An investor moving from a Mid-Cycle to a Late-Cycle outlook might:

- Reduce exposure to Technology and Discretionary.

- Increase exposure to Energy, Materials, and begin building a position in Staples and Healthcare.

Step 3: Execute and Monitor

Sector rotation is not a “set it and forget it” strategy. It requires ongoing monitoring of both your portfolio and the economic data. Rebalancing should be deliberate and based on a confirmed shift in the economic backdrop, not daily market noise. Avoid the temptation to overtrade.

Step 4: Choose Your Vehicles

- Sector ETFs: The most efficient tool for most investors. Examples include:

- Technology: XLK, VGT

- Financials: XLF, VFH

- Healthcare: XLV, VHT

- Consumer Discretionary: XLY, VCR

- …and so on for all 11 GICS sectors.

- Individual Stocks: For more advanced investors, selecting best-in-class companies within a leading sector can amplify returns but also carries higher idiosyncratic risk.

Read more: The Unsustainable Trajectory: A Look at the US National Debt and Its Global Implications

The Crucial Caveats: Risks and Limitations of Sector Rotation

No investment strategy is without flaw, and sector rotation carries significant risks that must be understood.

- The Timing Risk: This is the single greatest risk. It is incredibly difficult to correctly and consistently call the turns in the economic cycle. If you are early or late in your rotations, you can miss out on gains and amplify losses—a phenomenon known as “getting whipsawed.”

- The “This Time Is Different” Risk: Historical patterns are a guide, not a guarantee. Structural changes in the economy, geopolitical shocks (like a pandemic or war), or unprecedented monetary policy can disrupt the typical sector rotation sequence.

- Transaction Costs and Tax Inefficiency: Frequent trading generates commissions (though these are now minimal) and, more importantly, can create short-term capital gains, which are taxed at a higher rate than long-term gains.

- Overcomplication: For many investors, the complexity and required diligence of a sector rotation strategy may not be worth the marginal potential improvement over a simple, low-cost, diversified portfolio.

- The Rise of Mega-Cap Stocks: A handful of giant companies (e.g., Apple, Microsoft) now comprise a massive weight in the S&P 500 and span multiple sectors. A bet on the Technology sector is, in large part, a bet on these specific companies, which may not always behave in line with the broader sector’s historical tendencies.

Conclusion: A Strategic Compass, Not a Crystal Ball

Sector rotation is a powerful and intellectually rigorous framework for understanding the ebb and flow of the stock market. It encourages a macroeconomic perspective, instills discipline, and can help investors avoid the behavioral pitfalls of chasing performance or panicking during downturns.

However, it should not be viewed as a infallible trading system for market timing. Its true value lies in its use as a strategic compass.

For the tactical investor, it can provide a structured approach for tilting a portfolio toward areas of the market with a more favorable wind at their backs. For the long-term, buy-and-hold investor, understanding sector rotation provides invaluable context for the market’s movements, helping to explain why certain parts of their portfolio are performing well while others are not. This knowledge can foster the patience and conviction needed to stay the course.

Ultimately, whether you actively implement a rotation strategy or simply use it to inform your asset allocation, grasping the intimate link between the economic cycle and sector performance is a hallmark of a sophisticated and knowledgeable investor. In the ever-changing tides of the U.S. economy, that knowledge is a significant source of edge and confidence.

Read more: The Fed’s Next Move: Decoding the Path of Interest Rates in a Divided Economy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is sector rotation a suitable strategy for beginner investors?

A: Generally, no. Sector rotation requires a solid understanding of macroeconomic indicators, a willingness to monitor the economy actively, and a high tolerance for being wrong on timing. For beginners, a far more suitable and effective strategy is to build a diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds (e.g., an S&P 500 ETF or a Total Stock Market ETF) and contribute to it regularly. Mastering the basics of long-term investing is the essential first step.

Q2: How quickly should I rotate my sectors?

A: Sector rotation is a medium- to long-term tactical strategy, not a short-term trading one. Economic cycles typically last for years. Rotations should be considered when there is a sustained, confirmed shift in the economic data, not in response to a single month’s report or a market headline. Making one or two adjustments per year is more than enough for most practitioners.

Q3: Can I use sector rotation with my retirement account (e.g., 401(k))?

A: It depends on the investment options in your plan. Many 401(k) plans have limited choices, often only offering broad market funds or target-date funds. However, if your plan offers sector-specific mutual funds or if you have a self-directed brokerage window, it is possible. Be mindful that frequent trading in a retirement account doesn’t create a tax burden, but you should still be aware of any transaction fees or fund trading restrictions your plan may impose.

Q4: What’s the difference between a cyclical and a defensive sector?

A:

- Cyclical Sectors: Their performance is highly correlated with the strength of the economy. They tend to outperform during economic expansions and underperform during contractions. Examples include Consumer Discretionary, Technology, Industrials, and Financials.

- Defensive Sectors: Their performance is less tied to the economic cycle. They provide essential goods and services that people need regardless of economic conditions. They tend to be more stable and hold up better during recessions. Examples include Consumer Staples, Utilities, and Healthcare.

Q5: How does the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy impact sector rotation?

A: The Fed’s policy is a primary driver of the economic cycle and, therefore, sector rotation.

- Rate Cuts (Dovish Policy): Typically occur in the Early Cycle and Recession. This is a tailwind for rate-sensitive sectors like Real Estate and Utilities, and for growth sectors like Technology that benefit from lower discount rates on future earnings.

- Rate Hikes (Hawkish Policy): Typically occur in the Late Cycle. This is a headwind for growth and interest-rate-sensitive sectors but can be a benefit (up to a point) for sectors like Financials and Energy that can act as inflation hedges.

Q6: Are there any tools or resources to help me track the economic cycle for sector rotation?

A: Yes, several reputable sources provide the data needed:

- The Conference Board: Publishes the Leading Economic Indicators (LEI) index.

- Institute for Supply Management (ISM): Publishes the PMI reports for manufacturing and services.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS): For employment and inflation (CPI) data.

- Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED): A massive database of U.S. economic time series.

- Financial Media: Outlets like Bloomberg, Reuters, and The Wall Street Journal provide analysis of these data releases.

Q7: Does sector rotation work in other international markets?

A: The core principles of sector rotation are grounded in macroeconomics, so they are applicable globally. However, the specific sectors that lead and lag may differ based on the structure of a country’s economy (e.g., a commodity-exporting nation vs. a manufacturing-based one). The model outlined in this article is specifically tailored to the structure and dynamics of the U.S. economic cycle.