For decades, the landscape of corporate borrowing in the United States was dominated by a familiar institution: the traditional bank. A company seeking a loan would walk through the marble-clad doors of a commercial bank, present its financials, and negotiate terms with a relationship manager. This process, while sometimes slow, was the bedrock of corporate finance. But over the last 15 years, a seismic shift has occurred, largely away from the public eye. A new, powerful, and rapidly growing force has emerged from the shadows to challenge the old guard: the private credit market.

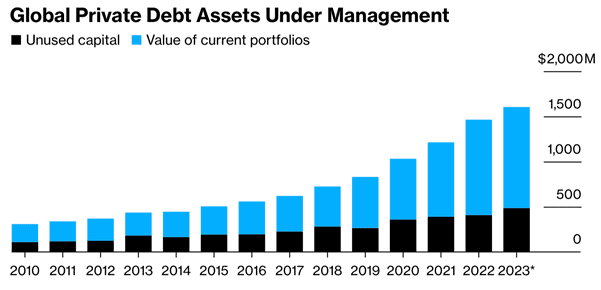

Often mischaracterized as a niche or alternative asset class, private credit has exploded into a $1.7 trillion global market, with the U.S. accounting for its largest share. It is the engine of modern “shadow banking”—a term for financial intermediaries that perform bank-like functions but operate outside the traditional, regulated banking system. This is not merely a trend; it is a fundamental restructuring of how mid-sized and large corporations access capital, with profound implications for the economy, investors, and the very nature of risk.

This article will demystify the private credit boom. We will explore its origins, its mechanics, the key players involved, and the compelling reasons for its rapid ascent. More importantly, we will analyze the profound implications—both the opportunities and the risks—of this tectonic shift in the financial landscape, providing a clear-eyed view of its future.

Understanding the Basics: What Exactly is Private Credit?

At its core, private credit involves non-bank lenders providing loans directly to companies. These loans are not syndicated, nor are they traded on public markets like bonds. They are privately negotiated, bespoke agreements between a borrower and a lender, which is typically a private equity firm, a dedicated credit fund, a business development company (BDC), or another institutional investment vehicle.

To distinguish it from other forms of lending, consider these key characteristics:

- Direct Origination: Loans are sourced and negotiated directly with the borrower, not acquired on the secondary market.

- Illiquidity: Unlike a publicly traded bond, a private credit loan is typically held until maturity. There is no deep, liquid market to easily sell it.

- Bespoke Terms: The covenants, structures, and terms are highly customized to the specific borrower and situation, offering lenders more control.

- Institutional Players: The lenders are almost exclusively large institutions like pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments, who can commit large sums of capital for long periods.

The most common types of private credit loans include:

- Direct Lending: The largest segment of the market. This involves providing senior secured loans (first in line for repayment) to mid-market companies, often to fund a private equity acquisition (a “leveraged buyout” or LBO).

- Mezzanine Debt: A hybrid of debt and equity, this is subordinated debt (second in line for repayment) that carries a higher interest rate and often includes warrants or options to buy equity in the company.

- Distressed/Special Situations: Providing financing to companies in or near bankruptcy, or undergoing a complex turnaround.

- Venture Debt: Loans provided to early-stage, venture-backed companies that are not yet profitable.

The Perfect Storm: The Catalysts for the Private Credit Boom

The rise of private credit was not an accident. It was the result of a convergence of powerful regulatory, economic, and structural forces that created a vacuum and then filled it.

1. The Regulatory Hammer: Post-2008 Banking Rules

The 2008 financial crisis was the single most significant catalyst. In its aftermath, regulators worldwide enacted a wave of new rules designed to make the banking system safer and more resilient. The Dodd-Frank Act in the U.S. and the Basel III international standards forced banks to:

- Hold More Capital: Banks were required to maintain higher levels of capital against their loans, making it more expensive for them to hold risky corporate debt on their balance sheets.

- Increase Liquidity: Rules ensured banks had enough easy-to-sell assets to withstand a funding crisis, which disincentivized holding long-term, illiquid loans.

- Face Stricter Scrutiny: Regulatory oversight intensified, with banks facing pressure to reduce their exposure to leveraged loans—the very lifeblood of private equity deals and corporate acquisitions.

As a result, traditional banks began to retreat from the “middle market”—companies with $50 million to $1 billion in EBITDA. This retreat created a massive funding gap, a multi-hundred-billion-dollar opportunity that non-bank lenders were perfectly positioned to seize.

2. The Investor Hunger for Yield

Concurrently, the post-2008 era ushered in a long period of historically low interest rates and quantitative easing. With yields on traditional fixed-income assets like government and corporate bonds falling to near-zero, institutional investors like pension funds and insurance companies were starved for returns. They have long-term liabilities and need to generate a certain level of income to meet their obligations.

Private credit offered an attractive solution. By providing illiquidity and complexity premiums, private credit funds could promise—and often deliver—returns of 8-12%, significantly higher than the 3-5% available from public leveraged loans or high-yield bonds. This “yield hunger” drove a massive inflow of capital into private credit funds, fueling their growth.

3. The Borrower’s Appeal: Speed, Certainty, and Discretion

From a corporate borrower’s perspective, private credit offers distinct advantages over the public markets or traditional bank syndicates.

- Speed and Certainty of Execution: A bank arranging a syndicated loan might need weeks to market the deal to other banks and investors, with the risk that market conditions sour or the deal fails to generate enough interest (“fails to clear”). A private credit deal, negotiated with a single lender or a small club of lenders, can be executed in a matter of days. This “certainty of close” is highly valued, especially in time-sensitive situations like acquisitions.

- Discretion: The terms of a private credit loan are confidential. For a company undergoing a restructuring or a sensitive acquisition, not having its financial details and loan covenants disseminated to thousands of public bondholders is a significant benefit.

- Flexibility and Partnership: Private credit lenders often position themselves as long-term partners. They are often more willing to structure creative solutions for a company’s unique needs, such as providing additional capital for an acquisition or allowing for temporary covenant relief during a rough patch—flexibility that is rare in the widely-syndicated public market.

The Ecosystem: Key Players and How a Deal Gets Done

To understand private credit in action, it’s essential to know the cast of characters and the typical flow of a transaction.

The Lenders:

- Private Debt Funds: These are the titans of the industry. Firms like Ares Management, Blackstone Credit, Blue Owl Credit, and Oaktree Capital manage multi-billion dollar funds dedicated to private credit. They raise capital from institutions and deploy it across direct lending, mezzanine, and distressed strategies.

- Business Development Companies (BDCs): These are publicly traded or non-traded vehicles that provide financing to small and mid-sized companies. They offer retail investors a way to access the private credit market and are a significant source of capital.

- Insurance Companies: Giants like Apollo, through its Athene annuities platform, and other insurers are major players. They have long-dated liabilities and need the higher-yielding, longer-duration assets that private credit provides, a strategy known as “private asset-liability management.”

The Borrowers:

- Private Equity-Backed Companies: This is the bread and butter of the direct lending market. When a private equity firm acquires a company, it uses a combination of its own equity and debt. Private credit funds have become the dominant source for this debt, financing thousands of LBOs.

- Non-Sponsored Companies: Increasingly, companies not owned by private equity are also turning to private credit for growth capital, refinancing existing debt, or acquisitions.

The Intermediaries:

- Investment Banks: While they may not provide the balance sheet, investment banks still play a crucial role as advisors, helping borrowers navigate the private credit landscape and negotiate terms.

A Typical Deal Flow: A Private Equity Buyout

- The Deal: A private equity firm decides to acquire “Company X” for $1 billion. It commits $400 million of its investors’ equity and needs to borrow $600 million in debt.

- The Mandate: Instead of going to a bank to syndicate a loan, the private equity firm approaches a private credit fund with which it has a relationship.

- Due Diligence: The credit fund conducts intense due diligence on Company X—its financials, market position, management team, and prospects.

- Term Sheet: The fund presents a term sheet outlining the loan amount, interest rate (often a base rate like SOFR + a spread of 5-7%), fees, and, most importantly, the covenants.

- Negotiation & Closing: After negotiations, the deal is signed. The private credit fund provides the $600 million loan, and the acquisition closes. The loan is held on the fund’s books, and the fund’s team actively monitors the investment.

The Implications: A Reshaped Financial Landscape

The ascendancy of private credit is not a neutral event. It has profound and wide-ranging consequences.

The Benefits: Filling a Void and Driving Efficiency

- Enhanced Capital Access: Private credit has undeniably expanded access to capital for a vast segment of the corporate universe that was being underserved by traditional banks. This fuels growth, innovation, and job creation within the vital mid-market sector.

- Financial System Diversification: By moving a significant portion of corporate lending outside the banking system, risk is theoretically spread across a wider base of institutional investors who are better equipped to bear it (due to long-term horizons and lack of depositor liabilities). This can make the financial system more resilient to a banking crisis.

- Disciplined Lending with Oversight: Private credit lenders, investing their own funds, are highly incentivized to conduct rigorous due diligence. Their hands-on, covenant-heavy approach can impose financial discipline on borrowers, potentially leading to better-managed companies.

The Risks and Concerns: The Shadows in Shadow Banking

However, the rapid, opaque growth of this market also raises significant concerns that regulators and investors are closely monitoring.

- Opacity and Systemic Risk: The “private” nature of these loans is a double-edged sword. Unlike a public bond, the terms and performance of these loans are not transparent. Regulators cannot easily assess the overall level of risk or leverage in the system. If a wave of defaults were to occur, it could trigger a fire sale in a market with no liquidity, potentially spilling over into the broader economy.

- Covenant-Lite Creep: In a competitive market with ample capital, lenders have been forced to relax their standards. The proliferation of “covenant-lite” loans—debt with fewer lender protections—has mirrored the trend in public markets. This means lenders have fewer early warning signs of trouble and less ability to intervene before a company fails.

- The Illiquidity Mismatch and Interest Rate Risk: Private credit funds offer periodic liquidity to their investors (e.g., quarterly or annual redemptions), but their assets are inherently illiquid. In a crisis, if too many investors try to exit at once, it could force a fund to freeze redemptions or sell assets at fire-sale prices. Furthermore, after years in a low-rate environment, the sector is now being tested by rising interest rates. While floating-rate loans protect lenders from rate hikes, they dramatically increase the debt-servicing burden for borrowers, raising the risk of defaults.

- Concentration and Economic Sensitivity: The private credit market is heavily exposed to the health of the private equity ecosystem and the broader economy. An economic downturn would simultaneously cause a rise in defaults in credit portfolios and a decline in the value of the private equity equity that supports it. Furthermore, the market is concentrated among a relatively small number of large asset managers, creating potential single points of failure.

Read more: Python vs. R for Data Analysis: Which Skill is More Valuable for US Jobs?

The Future of Private Credit: Mainstream, Not Alternative

Private credit is no longer an “alternative” asset class; it is a mainstream pillar of the global financial system. Its trajectory points toward continued growth and evolution.

- Market Expansion and Diversification: The strategies within private credit will continue to expand. We are seeing growth in areas like asset-based lending, real estate credit, and infrastructure debt. Furthermore, larger companies, even those with public ratings, are now tapping the private credit market for large, “mega-loans” of $1 billion or more, directly competing with the syndicated loan market.

- Increased Institutionalization and Scrutiny: As the market matures, the leading firms will become even larger and more sophisticated. With size comes increased regulatory and public scrutiny. While a full-scale bank-like regulation is unlikely, pressure for greater transparency and standardized reporting will intensify.

- The Test of a Downturn: The private credit market has grown spectacularly during a long period of economic expansion and low defaults. Its true resilience has not yet been tested by a severe, prolonged recession. How private credit lenders handle a wave of distressed companies—whether they act as constructive partners or aggressive liquidators—will define the industry’s long-term reputation and stability.

- Technological Disruption: Fintech and data analytics are beginning to play a larger role in due diligence and portfolio monitoring, potentially making the process more efficient and risk-aware.

Conclusion: A Permanent and Powerful Fixture

The private credit boom represents a fundamental and likely permanent reshaping of US corporate finance. Born from regulatory change and investor demand, it has effectively disintermediated the traditional bank for a large and important segment of the economy. It has provided critical capital to businesses, attractive yields to investors, and introduced a new source of dynamism and competition into the financial system.

Yet, its rise within the shadow banking system demands vigilance. The lack of transparency, the potential for hidden leverage, and the untested performance in a downturn are real concerns. The challenge for regulators, investors, and the industry itself is to harness the benefits of this powerful financial innovation while developing the frameworks to mitigate its inherent risks. One thing is certain: the era of walking into a local bank for a nine-figure loan is over. The future of corporate debt is private, direct, and here to stay.

Read more: The Top 5 Data Analytics Tools Dominating the US Market in 2025

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is private credit the same as private equity?

No, they are distinct asset classes. Private Equity primarily involves buying ownership stakes (equity) in companies, with the goal of growing the business and selling it for a profit. Private Credit involves lending money (debt) to companies. The private credit lender is a creditor, not an owner, and earns returns primarily through interest payments. However, they are closely intertwined, as private equity firms are the biggest borrowers from private credit funds.

Q2: How can an individual investor access the private credit market?

For most retail investors, direct access is difficult due to high minimum investments (often in the millions) and regulatory accreditation requirements. However, there are indirect ways:

- Business Development Companies (BDCs): These are publicly traded companies that invest primarily in private credit. You can buy shares of a BDC like any other stock on an exchange.

- Publicly Traded Private Credit Funds: Some large asset managers have listed funds or ETFs that provide exposure to the sector.

- Interval Funds: These are closed-end funds that offer periodic liquidity and often have allocations to private credit.

- It is crucial to understand that these investments carry significant risks, including illiquidity, volatility, and potential loss of capital. Consulting a financial advisor is essential.

Q3: What are “covenants,” and why are they important?

Covenants are rules and financial thresholds written into a loan agreement to protect the lender. They are early warning systems. For example, a covenant might require the borrower to maintain a certain level of profitability relative to its interest payments (an “interest coverage ratio”). If the borrower breaches a covenant, the lender has the right to intervene, which could involve renegotiating the loan, demanding immediate repayment, or taking control of the company. The shift towards “covenant-lite” loans removes these protections, giving lenders less control and allowing companies to take on more risk.

Q4: With rising interest rates, is private credit in a bubble?

This is a subject of intense debate. The floating-rate nature of most private credit loans protects lenders from inflation and rising rates, making them attractive in the current environment. However, the same rising rates put immense pressure on borrowers, increasing their interest expenses and the risk of default. Whether this leads to a crisis depends on the strength of the underlying economy and the underwriting discipline of the lenders. While pockets of the market may be overheated, many argue the asset class as a whole is not in a bubble but is entering a critical stress-testing period.

Q5: How is private credit regulated?

Private credit funds are not regulated like banks. They typically operate as private investment advisers, registered with the SEC but subject to a different, generally lighter, regulatory regime than depository institutions. They do not have to comply with bank capital requirements or liquidity rules. However, their rapid growth has put them on the radar of systemic risk regulators like the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), which is actively studying the potential risks they may pose to the financial system. Increased oversight and some form of enhanced regulation are likely in the future.

Q6: Who ultimately provides the capital for private credit loans?

The capital chain typically flows from ultimate savers to the borrowers. The primary sources of capital are:

- Public and Corporate Pension Funds

- Insurance Companies

- Sovereign Wealth Funds

- University Endowments and Foundations

- Family Offices and High-Net-Worth Individuals (through funds)

These entities allocate a portion of their massive investment portfolios to private credit funds, which then act as the managers, sourcing, underwriting, and managing the loans on their behalf.