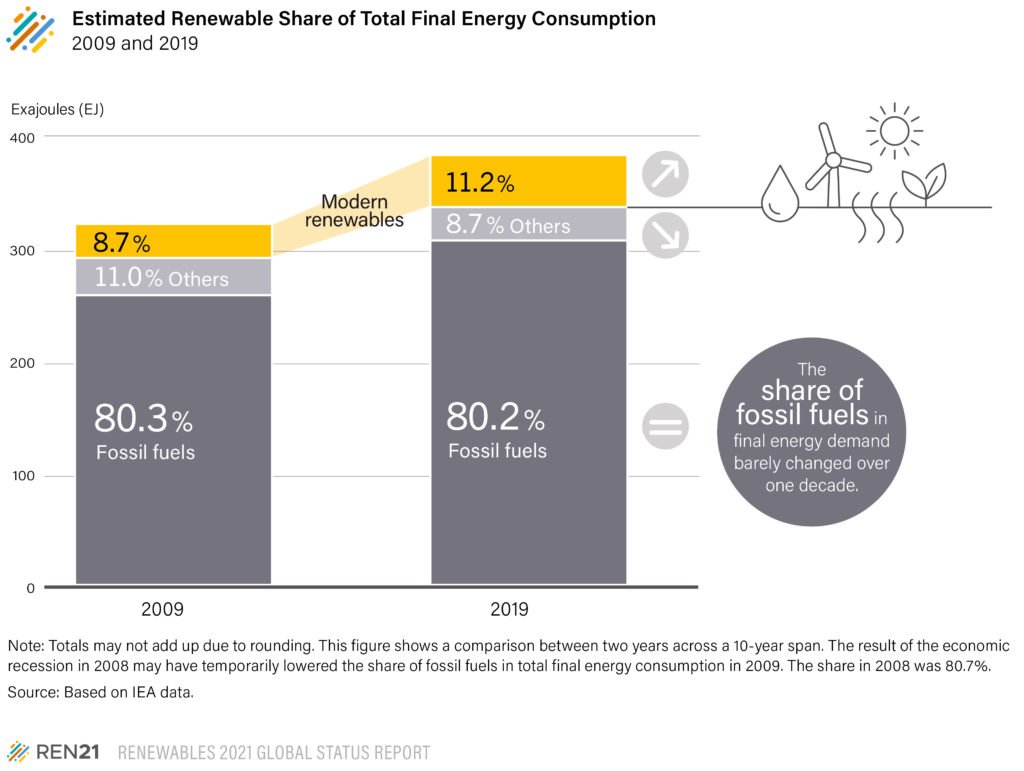

The United States stands at a historic inflection point. The urgent, scientifically-validated imperative to combat climate change is driving a profound shift from a fossil fuel-based economy to one powered by renewable energy. This “energy transition” is no longer a niche environmental concept but a central pillar of national policy, corporate strategy, and global finance. Trillions of dollars are being mobilized, technologies are advancing at a breakneck pace, and the very architecture of our energy systems is being rewired.

Yet, beneath the headlines of gigawatt-scale solar farms and burgeoning electric vehicle sales lies a more complex and critical question: Is this transition equitable?

In the world of finance and investment, “equity” has a dual meaning. It can refer to fairness and justice—ensuring that the benefits and burdens of the transition are shared broadly across society. Simultaneously, it refers to ownership stakes in companies—the shares that represent a claim on a corporation’s assets and earnings. This article will analyze the US energy transition through both lenses, focusing on the publicly traded companies at the heart of this transformation: the established titans of Oil & Gas (O&G) and the ascendant champions of Renewable Energy.

We will dissect the investment thesis for both sectors, moving beyond simplistic “good vs. evil” narratives to a nuanced examination of financial performance, risk exposure, growth trajectories, and valuation paradigms. This is not merely an academic exercise; it is a essential guide for investors, policymakers, and stakeholders seeking to navigate one of the most significant economic reallocations of our time.

Part 1: The Incumbent – A Deep Dive into the Oil & Gas Equity Landscape

For over a century, the Oil & Gas industry has been the bedrock of the global industrial economy, generating immense wealth and powering unprecedented development. In the US, the shale revolution of the last two decades cemented the nation’s status as an energy superpower. The equities of companies like ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips have long been core holdings in countless portfolios, prized for their dividends and scale.

1.1 The Traditional Investment Case for O&G

The historical appeal of O&G equities is built on a clear foundation:

- Proven Profitability and Cash Flow Generation: The business model, at its core, is straightforward: find, extract, and sell a commodity with inelastic demand. At stable or high prices, this generates enormous free cash flow (FCF).

- Shareholder Returns: A significant portion of this FCF is returned to shareholders through robust dividends and share buybacks. For income-focused investors, these dividends have been a reliable source of return, often yielding substantially more than the broader market.

- Economic Resilience and Geopolitical Relevance: Despite volatility, global demand for oil and gas remains structurally high, underpinned by transportation, industrial activity, and petrochemicals. O&G is also deeply intertwined with national security and geopolitics, providing a layer of implicit support.

- Scale and Infrastructure Moat: These companies possess unparalleled technical expertise, vast global infrastructure (pipelines, refineries, etc.), and balance sheets that can withstand commodity price cycles.

1.2 The Evolving Equity Story: Discipline, Decarbonization, and “Energy”

Post the 2020 price crash, the O&G sector underwent a profound shift in strategy. The mantra moved from “growth at all costs” to “capital discipline.” Companies slashed capital expenditures, prioritized debt reduction, and committed to returning more cash to shareholders. This new-found discipline has led to record profits and FCF in recent periods of high prices, bolstering their equity appeal in the short to medium term.

Simultaneously, the industry has embarked on a strategic pivot to address the energy transition, attempting to reframe itself as “energy” companies rather than just “oil” companies. This takes several forms:

- Investment in Lower-Carbon Fuels: Many majors are investing in biofuels, hydrogen, and renewable natural gas (RNG).

- Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS): This technology is a central pillar of many O&G decarbonization plans, aiming to capture emissions from industrial processes or directly from the air.

- Venture Capital and R&D: Companies like Chevron are allocating capital to venture funds that invest in breakthrough energy technologies.

- Emphasis on Natural Gas as a “Bridge Fuel”: Positioning gas, which emits roughly half the CO2 of coal when burned for power, as an essential partner to intermittent renewables.

1.3 The Multi-Faceted Risk Profile for O&G Equities

Despite this adaptation, O&G equities face a daunting and unique set of risks that are fundamentally reshaping their long-term valuation.

- Existential & Regulatory Risk: The core business is threatened by global climate policies aimed at phasing out fossil fuels. Litigation, carbon taxes, and drilling moratoria represent direct regulatory headwinds.

- ** Stranded Asset Risk:** A significant portion of a company’s proven reserves—its primary asset—may become uneconomical to extract in a carbon-constrained world, leading to massive write-downs.

- Market Volatility Risk: O&G equities are notoriously cyclical, tied to the volatile and often geopolitically-driven price of oil. This makes them unpredictable and unsuitable for risk-averse investors.

- Transition Execution Risk: There is significant skepticism about the scale and profitability of O&G companies’ green investments. Can a culture built on hydrocarbon extraction successfully innovate in fundamentally different technologies? The capital allocated to renewables is often a tiny fraction of that spent on maintaining the core business.

- Social License & ESG Pressure: The industry faces immense pressure from a growing cohort of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) investors. Pension funds and asset managers are increasingly divesting from fossil fuels, creating a potential long-term drag on share prices and increasing the cost of capital.

Part 2: The Challenger – Analyzing the Renewable Energy Equity Proposition

The renewable energy sector—encompassing solar, wind, geothermal, and the enabling infrastructure of energy storage and transmission—represents the future-facing side of the energy transition. Its equities, including companies like NextEra Energy, Brookfield Renewable Partners, and First Solar, have experienced explosive growth and captured the imagination of investors betting on a decarbonized world.

2.1 The Core Investment Thesis for Renewables

The bullish case for renewable energy equities is built on powerful, long-term macro trends:

- Exponential Cost Declines: The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar and wind has plummeted over the past decade, making them the cheapest source of new electricity generation in most parts of the world, even without subsidies. This is a fundamental economic driver.

- Policy Tailwinds: The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 is a landmark piece of legislation, providing unprecedented tax credits, grants, and loan guarantees for clean energy manufacturing and deployment. It has created a decade-long visibility for investment, de-risking projects and attracting massive capital inflows.

- Structural, Secular Growth Demand: The electrification of everything—from vehicles to home heating—is set to dramatically increase electricity demand. Concurrently, corporate decarbonization pledges (e.g., RE100) are creating a vast, voluntary market for renewable power purchase agreements (PPAs).

- Technological Innovation: Continuous improvements in solar panel efficiency, wind turbine size, and, crucially, battery storage technology are solving the problem of intermittency and making renewable-dominated grids a tangible reality.

2.2 The Business Models and Key Players

The renewable equity universe is diverse, comprising several distinct business models:

- Project Developers & Owners (e.g., NextEra Energy Resources): These companies build, own, and operate renewable energy assets, selling the power under long-term contracts to utilities or corporations. Their revenue is typically stable and contracted, resembling annuity-like cash flows.

- Manufacturers (e.g., First Solar, Enphase Energy): These firms manufacture the physical components of the energy transition: solar panels, wind turbines, inverters, and batteries. They are more exposed to commodity cycles, supply chains, and technological competition but offer higher growth potential.

- Yieldcos (e.g., Brookfield Renewable, Clearway Energy): These are publicly traded companies that own operating renewable assets and are structured to pass the vast majority of their cash flows to shareholders as dividends. They are designed for income-seeking investors who want exposure to the sector’s stable cash flows.

2.3 The Risk Profile of Renewable Equities

While the future appears bright, renewable energy equities are not without their own significant risks.

- Policy Dependence: The sector’s growth is heavily reliant on government policy. While the IRA provides strong support, political volatility and potential policy changes in the future remain a key risk.

- Supply Chain and Input Cost Volatility: Manufacturers and developers are vulnerable to disruptions in global supply chains (e.g., polysilicon for solar, critical minerals for batteries) and inflationary pressures, which can squeeze margins and delay projects.

- Execution and Interconnection Risk: Developing large-scale energy projects is complex. Permitting delays, local opposition, and, most critically, bottlenecks in connecting to the nation’s antiquated transmission grid can hamper growth and increase costs.

- Interest Rate Sensitivity: Renewable projects are highly capital-intensive upfront, with returns realized over decades. They are therefore sensitive to interest rates; rising rates increase the cost of capital and can depress valuations.

- Technological Disruption and Competition: The space is highly competitive, with rapid technological evolution. A company betting on a specific solar or battery chemistry could be rendered obsolete by a new breakthrough.

Part 3: The Equity Analysis – A Comparative Framework

To move beyond sector-level generalizations, we must compare the two asset classes directly across key financial and strategic metrics.

| Metric | Oil & Gas Equities | Renewable Energy Equities |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Trajectory | Mature/Declining: Facing long-term demand destruction. Growth is focused on specific niches (e.g., LNG) or financial engineering (buybacks). | High-Growth: Positioned in a sector with multi-decade, structural growth tailwinds driven by decarbonization and electrification. |

| Revenue Visibility | Low/Volatile: Tied directly to volatile commodity spot prices. | High/Stable: Often based on long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) with utilities or credit-worthy corporations, providing predictable cash flows. |

| Profitability & FCF | High, but Cyclical: Can generate enormous FCF at high commodity prices, but can turn negative during downturns. | Moderate & Stable: Lower margins than peak O&G, but more predictable and less cyclical. FCF is reinvested for growth or paid as dividends (Yieldcos). |

| Valuation Paradigm | Value/Dividend: Often valued on metrics like P/CF and FCF Yield. Valuation is heavily influenced by near-term commodity prices and dividend sustainability. | Growth/Asset-Based: Often valued on P/AUM (Assets Under Management) for Yieldcos or P/Sales and PEG ratios for manufacturers. Incorporates a premium for future growth. |

| Capital Allocation | High Shareholder Returns: Prioritizes dividends and buybacks. Capital expenditure is for maintenance and modest growth. | High Reinvestment: Prioritizes growth capital expenditure (CapEx) to build new projects and expand manufacturing capacity. Dividends are secondary (except for Yieldcos). |

| Primary Risks | Commodity price volatility, stranded assets, climate regulation, ESG divestment. | Policy changes, interest rates, supply chain disruptions, execution/permitting risk. |

3.1 The Convergence and Hybridization

The lines between these two sectors are beginning to blur, creating a new category of “energy” equities.

- O&G Companies Acquiring Renewables: BP’s acquisition of Lightsource bp and TotalEnergies’ massive renewable portfolio are examples of O&G majors using their balance sheets to buy their way into the transition.

- Utility-Scale Hybrids: A company like NextEra Energy is the world’s largest renewable energy developer but also operates a large, regulated utility in Florida. This model combines stable, regulated returns with high-growth, contracted renewables development.

- Focus on Enabling Technologies: Both sectors are converging on technologies like green hydrogen and advanced geothermal, which leverage subsurface expertise from O&G and renewable power sources.

This convergence suggests that the future of energy investing may not be a binary choice, but a portfolio construction challenge focused on companies with the best strategies and execution capabilities, regardless of their heritage.

Read more: The Biotech Bullseye: A Risk-Adjusted Analysis of Promising US Small-Cap Biotech Firms

Part 4: The Broader Equity Lens – A Just Transition for Society

The analysis thus far has focused on corporate equity. However, a truly comprehensive equity analysis of the energy transition must also consider its impact on societal equity—the fair distribution of its benefits and burdens.

A transition that only creates wealth for shareholders of renewable companies while leaving behind communities and workers dependent on the fossil fuel economy is not only unjust but also politically unsustainable.

Key Pillars of a Just Transition:

- Workforce Retraining and Redeployment: The skills of a roughneck on an oil rig are not directly transferable to a technician role on a solar farm. Significant public and private investment is needed in retraining programs to ensure fossil fuel workers have a pathway to the clean energy economy.

- Community Investment: Regions historically dependent on fossil fuel extraction, like Appalachia or parts of the Gulf Coast, face economic devastation. Proactive policies are needed to attract new clean energy manufacturing and projects to these areas, ensuring they are not left as “sacrifice zones.”

- Energy Affordability and Access: The transition must not exacerbate energy poverty. Low-income households spend a larger percentage of their income on energy. Policies must ensure that the benefits of cheaper renewable energy flow to these communities and that the costs of grid modernization are borne equitably.

- Environmental Justice: Fossil fuel infrastructure has disproportionately been located in low-income and minority communities, leading to adverse health outcomes. The build-out of new renewable energy projects and related infrastructure (e.g., transmission lines, battery storage facilities) must be done with robust community engagement to avoid perpetuating these historical inequities.

The Corporate Role: Both O&G and renewable companies have a role to play. O&G companies have a responsibility to support their workers and legacy communities through the transition. Renewable companies have a responsibility to embed equity from the start—through community benefit agreements, diverse hiring practices, and ensuring their supply chains are ethical and sustainable.

Conclusion: Navigating the Dual Mandate

The US energy transition is not a simple switch being flipped. It is a complex, multi-decade, capital-intensive rewiring of the world’s largest economy. For investors, this presents a dual mandate: to seek competitive financial returns while also understanding and contributing to a transition that is equitable for both shareholders and society at large.

The investment landscape is not a binary choice between “dirty” O&G and “clean” Renewables. It is a spectrum. The incumbent O&G sector offers value, high cash returns, and a potential (though contested) bridge to the future, all while carrying existential long-term risks. The renewable sector offers explosive growth, policy tailwinds, and alignment with global decarbonization goals, but it faces its own challenges of execution, valuation, and interest rate sensitivity.

The most prudent strategy may be a dynamic and discerning one. It involves:

- Selecting resilient O&G companies with strong balance sheets, a credible decarbonization strategy, and a commitment to capital discipline.

- Identifying leading renewable companies with proven execution capabilities, technological moats, and access to capital.

- Focusing on the enablers—companies building the transmission grid, advanced battery storage, and other critical infrastructure.

Ultimately, a successful and equitable energy transition—one that generates wealth for investors while fostering a healthier, more just, and sustainable society—is the defining challenge and opportunity of our generation. By analyzing both meanings of “equity” with clarity and rigor, we can all play a more informed role in shaping its outcome.

Read more: Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) Rebound: A Sector-by-Sector Analysis Post-Fed Hikes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Can Oil & Gas companies truly transition to becoming “energy” companies, or is it mostly greenwashing?

This is the central question for the sector. The answer is nuanced. There is a spectrum of commitment. Some companies are making substantial, strategic bets on low-carbon technologies (e.g., BP, Shell, TotalEnergies), while others are focusing primarily on their core O&G business with smaller, ancillary investments in decarbonization (e.g., CCUS). The scale of their renewable investments is still a small fraction of their overall CapEx. The key for investors is to scrutinize capital allocation plans, set transparent targets, and track progress against those targets to separate rhetoric from reality.

Q2: With the volatility in renewable stocks, are they really a safer long-term bet than Oil & Gas?

“Safer” depends on the timeframe and type of risk. O&G stocks are unsafe due to commodity price volatility and long-term existential risk. Renewable stocks are unsafe due to interest rate sensitivity, policy risk, and execution risk. However, the long-term secular demand trend for renewables is almost universally seen as upward, while for oil it is increasingly uncertain. For a long-term investor, the renewable sector’s alignment with global decarbonization goals may provide a different kind of “safety” through growth visibility, albeit with significant short-term price volatility.

Q3: How does the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) change the investment calculus for both sectors?

The IRA is a game-changer, but for each sector differently.

- For Renewables: It is a massive accelerant. It provides long-term certainty through extended tax credits, adds bonuses for using domestic content and locating projects in “energy communities,” and creates new incentives for standalone storage and green hydrogen. It dramatically de-risks project economics.

- For Oil & Gas: The IRA is more of a mixed bag. It includes provisions that benefit the industry, primarily through tax credits for CCUS and hydrogen. This allows O&G companies to potentially generate revenue from decarbonizing their operations. However, it also includes a fee on methane emissions, which is a direct cost. Overall, it incentivizes O&G companies to participate in the transition through specific technologies.

Q4: What are “Yieldcos” and how are they different from traditional energy stocks?

Yieldcos are a specific type of equity structure designed for income-focused investors. They are publicly traded companies that own a portfolio of operating, cash-flowing renewable energy assets (e.g., solar farms, wind parks). Their key feature is that they are structured to pass the majority of their stable, contracted cash flows to shareholders as dividends. They are less focused on high growth and more on predictable, growing dividends, making them analogous to utility or infrastructure stocks rather than high-growth tech stocks.

Q5: What does a “Just Transition” mean for an average investor?

For the average investor, supporting a Just Transition means incorporating social and governance factors into their investment decisions, alongside environmental ones. This can involve:

- Investing in companies with strong labor practices, community engagement policies, and commitments to a diverse workforce.

- Supporting ESG funds that explicitly screen for just transition principles.

- Engaging as a shareholder by voting on proxy proposals related to worker retraining, community benefits, and environmental justice reporting.

- Understanding that a transition that creates social unrest or leaves millions behind is a systemic risk that ultimately threatens all investments, including their portfolio.

Q6: Are there ETFs or mutual funds that provide a balanced exposure to the entire energy transition?

Yes, the financial industry has created numerous products to capture this theme. Instead of picking individual winners, investors can buy into funds that hold a basket of companies involved in the transition. These include:

- Broad Clean Energy ETFs: e.g., iShares Global Clean Energy ETF (ICLN), Invesco Solar ETF (TAN).

- Infrastructure ETFs: which include companies building the grid and other enabling infrastructure.

- Thematic ETFs: focused on specific technologies like hydrogen or carbon capture.

- Some actively managed mutual funds are now explicitly focused on the “energy transition” theme, blending select O&G companies with strong transition plans alongside pure-play renewable and tech companies.